# Molecular Dynamics

[](https://crates.io/crates/dynamics)

[](https://docs.rs/dynamics)

[](https://www.athanorlab.com/docs/md.html)

[](https://pypi.org/project/mol_dynamics)

A Python and Rust library for molecular dynamics. Compatible with Linux, Windows, and Mac. Uses CPU with threadpools and

SIMD, or an Nvidia GPU. It uses traditional forcefield-based molecular dynamics, and is inspired by Amber. It does not

use quantum-mechanics, nor ab-initio methods.

It uses the [Bio-Files](https://github.com/david-oconnor/bio-files) dependency to load molecule and force-field files.

This readme is a general overview, and focuses on code examples integration into application, and code examples. For

more information about the algorithm, reference the [docs here](https://www.athanorlab.com/docs/md.html). Please

reference the [API documentation](https://docs.rs/dynamics) for details on the functionality of each data structure and

function. You may wish to reference the [Bio Files API docs](https://docs.rs/bio-files) as well.

We recommend running this on GPU; it's much faster. This requires an Nvidia GPU Rtx3 series or newer, with Nvidia

drivers 580 or newer.

**Note: The Python version does not yet use GPU for long-range forces**. We would like to fix this, but are having

trouble linking the cuFFT dependency.

## Use of this library

This is intended for integration into a Rust or Python program, another Rust or Python library, or in small scripts that

describe a workflow. When scripting, you will likely load molecule files directly, use integrated force fields or load

them from file, and save results to a reporter format like DCD. If incorporating into an application, you might do more

in memory using the [data structures](https://docs.rs/dynamics/latest/dynamics/) we provide.

Our API goal is to both provide a default terse syntax with safe defaults, and allow customization and flexibility that

facilitates integration into bigger systems.

## Goals

- Runs Newtonian MD algorithms accurately

- Easy to install, learn, and use

- Fast

- Easy integration into workflows, scripting, and applications

## Installation

Python: `pip install mol-dynamics`

Rust: Add `dynamics` to `Cargo.toml`. Likely `bio_files` as well.

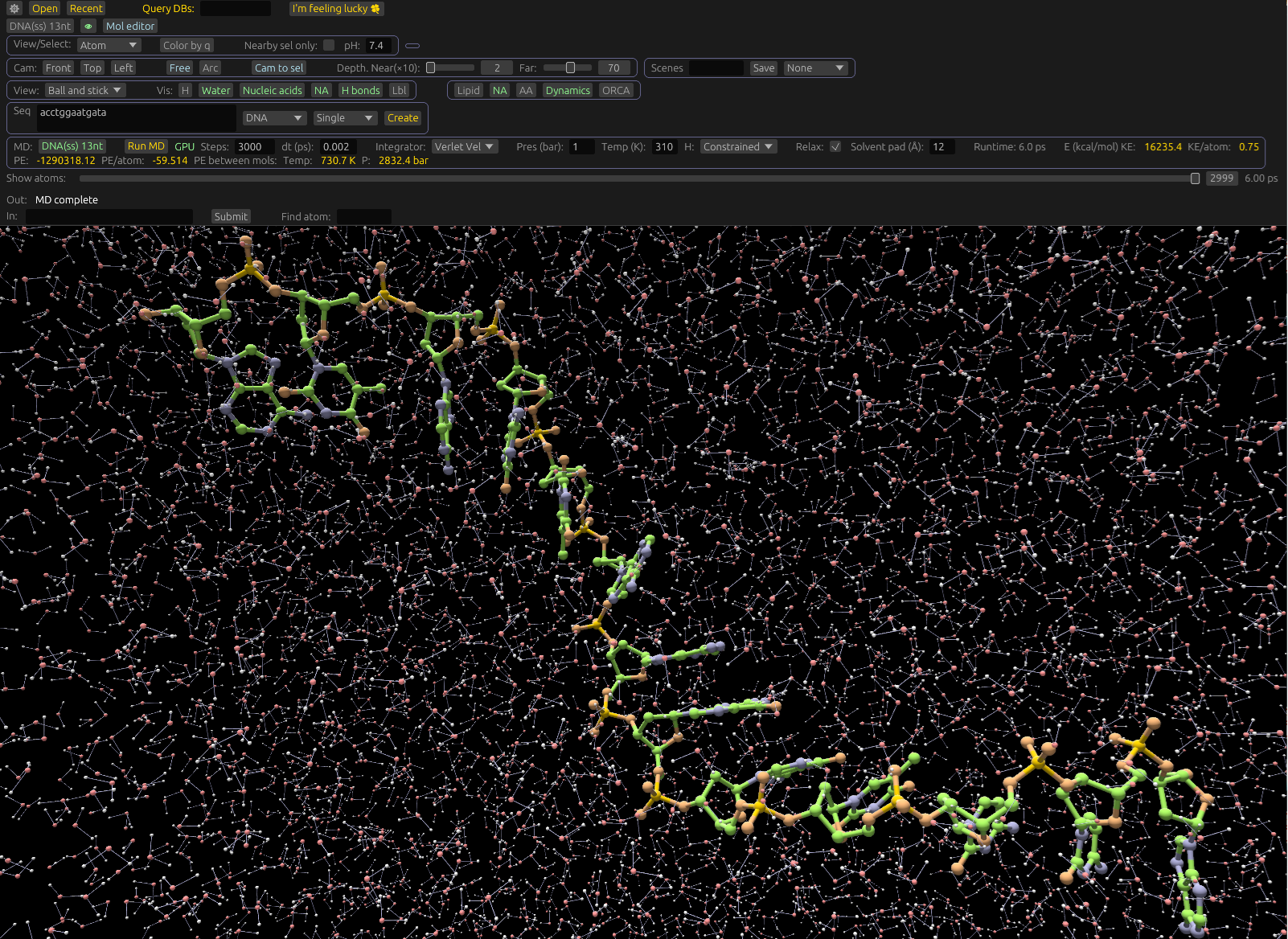

For a GUI application that uses this library, download

the [Molchanica software](https://github.com/david-oconnor/molchanicaa) This provides an easy-to-use way to set up the

simulation, and play back trajectories.

## Input topology

The simulation accepts sets of [AtomicGeneric](https://docs.rs/bio_files/latest/bio_files/struct.AtomGeneric.html)

and [BondGeneric](https://docs.rs/bio_files/latest/bio_files/struct.BondGeneric.html). You can get these by loading

molecular file formats (mmCIF, Mol2, SDF, etc) using the [Bio Files](https://github.com/david-OConnor/bio_files)

library ([biology-files in Python](https://pypi.org/project/biology-files/)), or by creating them directly. See examples

below and in the [examples folder](https://github.com/David-OConnor/dynamics/tree/main/examples), and the docs links

above; those are structs of plain data that can be built from from arbitrary input sources. For example, if you're

building an application, you might use a more complicated Atom format; you can create a function that converts between

yours, and `AtomGeneric`.

## Parameters

It integrates the following [Amber parameter sets](https://ambermd.org/AmberModels.php):

- Small organic molecules, e.g. ligands: [General Amber Force Fields: GAFF2](https://ambermd.org/antechamber/gaff.html)

- Protein/AA: [FF19SB](https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00591)

- Nucleic acids: [OL24](https://fch.upol.cz/ff_ol/refinements.php)

and [RNA/OL3](https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ct200162x) libraries

- Lipids: Lipid21

- Carbohydrates: GLYCAM_06j

- Water: [OPC](https://arxiv.org/abs/1408.1679)

## The algorithm

This library uses a traditional MD workflow. We use the following components:

### Integrators, thermostats, barostats

We provide a Velocity-Verlet integrator. It can be used with a Berendsen barostat, and either

a [CSVR](https://arxiv.org/pdf/0803.4060), or Langevin Middle thermostat. Or, use the Velocity Verlet integrator

without a thermostat. These continuously update atom velocities (for molecules and solvents) to match target pressure

and temperatures. You can select the target temperature to the right of the integrator selector.

The Verlet Velocity integrator can be either used with CSVR thermostat, or without; this is selected using the

*thermostat* checkbox next to the integrator selector. At this time, the thermostat temperature constant, τ, is

hard-coded to be 0.9ps. Lower values correct more aggressively.

The Langevin Middle integrator is selected by default, and is always used with a thermostat. Its coefficient γ is

selectable in the UI, next to the integrator selector, and is in 1/ps. Higher γ values correct to the target temperature

more aggressively.

## Solvation

We use an explicit water solvation model: A 4-point rigid OPC model, with a point partial charge on each Hydrogen, and a

M (or EP) point offset from the Oxygen.

We use the [SETTLE](https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jcc.540130805) algorithm to maintain rigidity, while

applying forces to each atom. Only the Oxygen atom carries a Lennard Jones(LJ) force. Solvation is set up by default,

and requires no special adjustments. If you wish, you may change the size of the simulation box padding with its

associated input on the MD toolbar.

The simulation box uses periodic boundary conditions: When a water molecule exits one side of it, it simultaneously

re-appears on the opposite side. Further, our long-range SPME computations are designed to incorporate this periodic

boundary position, simulating an infinitely-extending simulation box. Note that this has an unfortunate (But usually

negligible) side effect of also including *images* of non-water molecules in computations.

## Equilibration

Prior to the simulation properly starting, we perform equilibration with two techniques: Iterative energy minimization

of the (non-water) molecules, and running a short simulation of only the water molecules. The minimization helps to

relieve tension in the initial atom configuration. For example, if the bond length provided by the initial atom

coordinates doesn't match that of the *bonded* length parameter.

The water pre-simulation breaks the initial crystal lattice configuration, builds hydrogen bond networks, and allows the

simulation to settle at the specific temperature. We initialize water molecules with appropriate velocities, but this

additional step helps. When the snapshots (aka trajectories) start building, the system will be equilibrated.

You can disable the energy minimization using the *relax* check box in the UI, but the water equilibration is always

active. It runs in the range of a few hundred to 1,000 steps, and uses a more aggressive thermostat coefficient (τ for

CSVR, and γ for Langevin) than is used during the normal simulation.

## Bonded forces

We use Amber-style spring-based forces to maintain covalent bonds. We maintain the following parameters:

- Bond length between each covalently-bonded atom pair

- Angle (sometimes called valence angle) between each 3-atom line of covalently-bonded atoms. (4atoms, 2 bonds)

- Dihedral (aka torsion) angles between each 4-atom line of covalently-bonded atoms. (4 atoms, 3 bonds).

These usually have rotational symmetry of 2 or 3 values which are stable.

- Improper Dihedral angles between 4-atoms in a hub-and-spoke configuration. These, for example, maintain stability

- where rings meet other parts of the molecule, or other rings.

## Non-bonded forces

These are Coulomb and Lennard Jones (LJ) interactions. These make up the large majority of computational effort. Coulomb

forces represent electric forces occurring from dipoles and similar effects, or ions. We use atom-centered pre-computed

partial charges for these. They occur within a molecule, between molecules, and between molecules and solvents.

We use a neighbors list (Sometimes called Verlet neighbors; not directly related to the Verlet integrator) to reduce

computational effort. We use

the [SPME Ewald](https://manual.gromacs.org/nightly/reference-manual/functions/long-range-electrostatics.html)

approximation to reduce computation time. This algorithm

is suited for periodic boundary conditions, which we use for the solvent.

We use Amber's scaling and exclusion rules: LJ and Coulomb force is reduced between atoms separated by 1 and 2 covalent

bonds, and skipped between atoms separated by 3 covalent bonds.

We have two modes of handling Hydrogen in bonded forces: The same as other atoms, and rigid, with position maintained

using SHAKE and RATTLE algorithms. The latter allows for stability under higher timesteps. (e.g. 2ps)

## Center-of-mass drift removal

Periodically we remove any linear and angular center of mass drift, that applies to the whole system. This helps reduce

extra energy in the system that may have entered from numerical precision and other error sources. We apply this to both

water, and non-water molecules.

## Velocity initiation and maintenance

Water molecules are initiated with velocities according to

the [Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maxwell%E2%80%93Boltzmann_distribution), according to

the prescribed target temperature. This temperature is specified in the UI. Prior to our proper simulation start time,

we briefly perform MD on water molecules only, holding the solute rigid. This allows hydrogen bond networks to form, and

lets the thermostat fine-tune the velocities.

## Partial Charges

For proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, we use partial charges provided by Amber force fields (listed above) directly.

For small organic molecules, we infer [AM1-BCC partial charges](https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jcc.10128)

for each molecule when loading it. We do so using a machine learning algorithm trained on Amber's Geostd set. We use

the [candle](https://github.com/huggingface/candle) library's neural nets. It's trained on this set of ~30k small

organic molecules that have force field types, and partial charges assigned using AM1-BCC computations. Inference is

fast, typically taking a few milliseconds.

If your small molecule already has partial charges, we use those directly instead of computing new ones. Partial charges

may be provided in Mol2 files as part of their column data, or as SDF metadata. For the latter, we support both

*OpenFF*'s "atom.dprop.PartialCharge", and *Pubchem*'s "PUBCHEM_MMFF94_PARTIAL_CHARGES" formats.

If ORCA is installed, you can use it to generate [MBIS](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1608.05556) charges. This is one of the

most accurate approaches, but is very slow; it may take several minutes to complete for a single small molecule. To use

this, click *Assign MBIS q* from the *ORCA* UI section; it will update charges for the active molecule. You may then

save this to `Mol2` or `SDF` format if you wish. When saving to SDF, we use the Pubchem metadata format

for partial charges.

## Bonded parameter overrides for small organic molecules

Small organic molecules use bonded parameters from Amber's Gaff2 set. Most molecules have dihedral parameters (proper

and improper) that are not present in Gaff2. We substitute Gaff2 parameters in for these based on the closest match

of their force field types to parameters present in Gaff2. We (rarely) do the same for missing bond and valence angle

parameters. Alternatively, you may provide these overrides directly by opening *FRDMOD* or

*PRMPTOP* files directly.

## Floating point precision

This application uses mixed precision: 32-bit floating point is the default for most operations. We use 64-bit for

accumulation computations (e.g. kinetic and potential energy), and in thermostat and barostat computations. The use of

32-bit floating point introduces more precision errors than 64-bit, but reduces memory and bandwidth cost. This is

especially relevant for parallel computations: The CPU can perform twice as many 32-bit SIMD operations are 64-bit, and

bandwidth to and from the GPU on the PCIe bus is halved. Perhaps more importantly, consumer GPUs have poor f64

performance, so using 32-bit values significantly improves speed on these devices.

### How pH adjustment works

pH in proteins is represented by the protenation state of certain amino acids. In particular, His,

Asp, Cys, Glu, and Lys are affected. These changes are affected in utility functions we provide that

add Hydrogen atoms.

## Energy, temperature, and pressure measurements

Snapshots contain energy data. Potential energy is broken down into two components: That from covalent bonds (*Bonded*),

and that from Coulomb, Lennard Jones, and SPME forces. (*Non-bonded*) These values all take into account both the

molecules loaded, and the explicit water solvent molecules. Water molecules are treated as any other, with some

exceptions due to their rigidly-defined geometry.

Kinetic energy is computed using the standard manner: By computing the mass of each atom multiplied by the magnitude

squared of its velocity, summed over every atom. Temperature, displayed in Kelvin, is computed as follows:

$2 KE / (**DOF** × **R**) $ , where **R** is the Boltzmann gas constant, defined as 1.987 × 10³ kcal mol⁻¹ K⁻¹. (These

are the simulation's native units).

**DOF** is the number of degrees-of-freedom of the system. We compute this as 3 × the number of non-static atoms in the

system excluding water, for the 3 orthogonal directions an atom can move. We add 6 × the number of water molecules in

the system; this takes into account its rigid character, with each water molecule having 3 positional degrees of

freedom, and 3 rotational ones. We subtract one degree of freedom for each non-water hydrogen atom, if hydrogens are set

as constrained. We also subtract 3 DOF for the center-of-motion drift removal, and 3 for its angular motion removal.

### Saving results

Snapshots of results can be returned in memory, or saved to disk

in [DCD](https://docs.openmm.org/7.1.0/api-python/generated/simtk.openmm.app.dcdfile.DCDFile.html) format.

## More info

We plan to support carbohydrates and lipids later. If you're interested in these, please add a Github Issue.

These general parameters do not need to be loaded externally; they provide the information needed to perform

MD with any amino acid sequence, and provide a baseline for dynamics of small organic molecules.

This program can automatically load ligands with Amber parameters, for the

*Amber Geostd* set. This includes many common small organic molecules with force field parameters,

and partial charges included. It can infer these from the protein loaded, or be queried by identifier.

You can load these molecules with parameters directly from the GUI by typing the identifier.

If you load an SDF molecule, the program may be able to automatically update it using Amber parameters and

partial charges.

For details on how dynamics using this parameterized approach works, see the

[Amber Reference Manual](https://ambermd.org/doc12/Amber25.pdf). Section 3 and 15 are of particular

interest, regarding force field parameters.

We load partial charges for ligands from *mol2*, *PDBQT* etc files. Protein dynamics and water can be simulated

using parameters built-in to the program (The Amber one above). For small organic molecules, we infer force field

params, and partial charges for each atom, as well as molecule-specific *frcmod* overrides from GAFF2: Generally, this

is proper and improper dihedral angles. It is, occasionally, bond and angle parameters.

You can load (and save) combined atom and forcefield data from Amber PRMTOP files; these combine

these two data types into one file.

Use the code below, the [Examples folder on Github](https://github.com/David-OConnor/dynamics/tree/main/examples),

and the [API documentation](https://docs.rs/dynamics) to learn how to use it. General workflow:

-Create a [MdState struct](https://docs.rs/dynamics/latest/dynamics/struct.MdState.html) with `MdState::new()`.

This accepts a [configuration](https://docs.rs/dynamics/latest/dynamics/struct.MdConfig.html), the molecules to

simulate,

and force field parameters.

Run a simulation step by calling `MdState::step()`. This

accepts [an enum which defines the computation devices](https://docs.rs/dynamics/latest/dynamics/enum.ComputationDevice.html)

(CPU/GPU), and the time step in picoseconds. This step can be called as required for your application. For example

you can call it repeatedly in a loop, or as required, e.g. to not block a GUI, or for interactive MD.

Example use (Python):

```python

from mol_dynamics import *

def setup_dynamics(mol: Mol2, protein: MmCif, param_set: FfParamSet) -> MdState:

"""

Set up dynamics between a small molecule we treat with full dynamics, and a rigid one

which acts on the system, but doesn't move.

"""

# Or, consider using these terse helpers instead for small organic molecules.

# MolDynamics.from_amber_geostd("CPB") # Can use with a PubChem CID as well.

# MolDynamics.from_mol2(mol, lig_specific)

# MolDynamics.from_sdf(mol, lig_specific)

mols = [

MolDynamics(

ff_mol_type=FfMolType.SmallOrganic,

atoms=mol.atoms,

# Pass a [Vec3] of starting atom positions. If absent,

# will use the positions stored in atoms.

atom_posits=None,

atom_init_velocities=None,

bonds=mol.bonds,

# Pass your own from cache if you want, or it will build.

adjacency_list=None,

static_=False,

mol_specific_params=None,

bonded_only=False,

),

MolDynamics(

ff_mol_type=FfMolType.Peptide,

atoms=protein.atoms,

atom_posits=None,

atom_init_velocities=None,

bonds=[], # Not required if static.

adjacency_list=None,

static_=True,

mol_specific_params=None,

bonded_only=False,

),

]

return MdState(

MdConfig(),

mols,

param_set,

)

def main():

mol = Mol2.load("CPB.mol2")

protein = MmCif.load("1c8k.cif")

param_set = FfParamSet.new_amber()

# Optional; the library infers FRCMOD overrides on its own.

_lig_specific = ForceFieldParams.load_frcmod("CPB.frcmod")

# Or, instead of loading atoms and mol-specific params separately:

# mol, lig_specific = load_prmtop("my_mol.prmtop")

# Add Hydrogens, force field type, and partial charge to atoms in the protein; these usually aren't

# included from RSCB PDB. You can also call `populate_hydrogens_dihedrals()`, and

# `populate_peptide_ff_and_q() separately. Add bonds.

_bonds, _dihedrals = prepare_peptide_mmcif(

protein,

param_set.peptide_ff_q_map,

7.0,

)

# A variant of that function called `prepare_peptide` takes separate atom, residue, and chain

# lists, for flexibility.

md = setup_dynamics(mol, protein, param_set)

n_steps = 100

dt = 0.002 # picoseconds.

for _ in range(n_steps):

md.step(dt)

snap = md.snapshots[len(md.snapshots) - 1] # A/R.

print(f"KE: {snap.energy_kinetic}, PE: {snap.energy_potential}, Atom posits:")

for posit in snap.atom_posits:

print(f"Posit: {posit}")

# Also keeps track of velocities, and water molecule positions/velocity

# Do something with snapshot data, like displaying atom positions in your UI.

# You can save to DCD file, and adjust the ratio they're saved at using the `MdConfig.snapshot_setup`

# field: See the example below.

for snap in md.snapshots:

pass

main()

```

Example use (Rust):

```rust

use std::path::Path;

use bio_files::{MmCif, Mol2, md_params::ForceFieldParams};

use dynamics::{

ComputationDevice, FfMolType, MdConfig, MdState, MolDynamics,

params::{FfParamSet, prepare_peptide},

populate_hydrogens_dihedrals,

};

/// Set up dynamics between a small molecule we treat with full dynamics, and a rigid one

/// which acts on the system, but doesn't move.

fn setup_dynamics(

dev: &ComputationDevice,

mol: &Mol2,

protein: &MmCif,

param_set: &FfParamSet,

) -> MdState {

// Or, consider using these terse helpers instead for small organic molecules.

// MolDynamics::from_amber_geostd("CPB").unwrap(); // Can use with a PubChem CID as well.

// MolDynamics::from_mol2(&mol, Some(lig_specific)).unwrap();

// MolDynamics::from_sdf(&mol, Some(lig_specific)).unwrap();

let mols = vec![

MolDynamics {

ff_mol_type: FfMolType::SmallOrganic,

atoms: mol.atoms.clone(),

// Pass a &[Vec3] of starting atom positions. If absent,

// will use the positions stored in atoms.

atom_posits: None,

atom_init_velocities: None,

bonds: mol.bonds.clone(),

// Pass your own from cache if you want, or it will build.

adjacency_list: None,

static_: false,

mol_specific_params: None,

bonded_only: false,

},

MolDynamics {

ff_mol_type: FfMolType::Peptide,

atoms: protein.atoms.clone(),

atom_posits: None,

atom_init_velocities: None,

bonds: Vec::new(), // Not required if static.

adjacency_list: None,

static_: true,

mol_specific_params: None,

bonded_only: false,

},

];

MdState::new(dev, &MdConfig::default(), &mols, param_set).unwrap()

}

fn main() {

let dev = ComputationDevice::Cpu;

let param_set = FfParamSet::new_amber().unwrap();

let mut protein = MmCif::load(Path::new("1c8k.cif")).unwrap();

let mol = Mol2::load(Path::new("CPB.mol2")).unwrap();

// Optional; the library infers FRCMOD overrides on its own.

let _mol_specific = ForceFieldParams::load_frcmod(Path::new("CPB.frcmod")).unwrap();

// Or, instead of loading atoms and mol-specific params separately:

// let (mol, lig_specific) = load_prmtop("my_mol.prmtop");

// Add Hydrogens, force field type, and partial charge to atoms in the protein; these usually aren't

// included from RSCB PDB. You can also call `populate_hydrogens_dihedrals()`, and

// `populate_peptide_ff_and_q() separately. Add bonds.

let (_bonds, _dihedrals) = prepare_peptide_mmcif(

&mut protein,

¶m_set.peptide_ff_q_map.as_ref().unwrap(),

7.0,

)

.unwrap();

// A variant of that function called `prepare_peptide` takes separate atom, residue, and chain

// lists, for flexibility.

let mut md = setup_dynamics(&dev, &mol, &protein, ¶m_set);

let n_steps = 100;

let dt = 0.002; // picoseconds.

for _ in 0..n_steps {

md.step(&dev, dt);

}

let snap = &md.snapshots[md.snapshots.len() - 1]; // A/R.

println!(

"KE: {}, PE: {}, Atom posits:",

snap.energy_kinetic, snap.energy_potential

);

for posit in &snap.atom_posits {

println!("Posit: {posit}");

// Also keeps track of velocities, and water molecule positions/velocity

}

// Do something with snapshot data, like displaying atom positions in your UI.

// You can save to DCD file, and adjust the ratio they're saved at using the `MdConfig.snapshot_setup`

// field: See the example below.

for snap in &md.snapshots {}

}

```

Example of loading your own parameter files:

```python

param_paths = ParamGeneralPaths(

peptide="parm19.dat",

peptide_mod="frcmod.ff19SB",

peptide_ff_q="amino19.lib",

peptide_ff_q_c="aminoct12.lib",

peptide_ff_q_n=None,

small_organic="gaff2.dat",

lipids="lipid21.dat",

)

param_set = FfParamSet(param_paths)

```

```rust

let param_paths = ParamGeneralPaths {

peptide: Some( & Path::new("parm19.dat")),

peptide_mod: Some( & Path::new("frcmod.ff19SB")),

peptide_ff_q: Some( & Path::new("amino19.lib")),

peptide_ff_q_c: Some( & Path::new("aminoct12.lib")),

peptide_ff_q_n: Some( & Path::new("aminont12.lib")),

small_organic: Some( & Path::new("gaff2.dat")),

lipids: Some( & Path::new("lipid21.dat")),

..default ()

};

let param_set = FfParamSet::new( & param_paths);

```

An overview of configuration parameters. You may wish to (Rust) use a baseline of the `Default` implementation,

then override specific fields you wish to change.

```rust

let cfg = MdConfig {

// Defaults to Langevin middle.

integrator: dynamics::Integrator::VelocityVerlet,

// If enabled, zero the drift in center of mass of the system.

zero_com_drift: true,

// Kelvin. Defaults to 310 K.

temp_target: 310.,

// Bar (Pa/100). Defaults to 1 bar.

pressure_target: 1.,

// Allows constraining Hydrogens to be rigid with their bonded atom, using SHAKE and RATTLE

// algorithms. This allows for higher time steps.

hydrogen_constraint: dynamics::HydrogenConstraint::Fixed,

// Deafults to in-memory, every step

snapshot_handlers: vec![

SnapshotHandler {

save_type: SaveType::Memory,

ratio: 1,

},

SnapshotHandler {

save_type: SaveType::Dcd(PathBuf::from("output.dcd")),

ratio: 10,

},

],

sim_box: SimBoxInit::Pad(10.),

// Or sim_box: SimBoxInit::Fixed((Vec3::new(-10., -10., -10.), Vec3::new(10., 10., 10.)),

};

```

Python config syntax:

```python

cfg = MdConfig() // Initializes with defaults.

cfg.integrator = dynamics.Integrator.VelocityVerlet

cfg.temp_target = 310.

# etc

```

You can run `md_state.computation_time()` after running to get a breakdown of how long each computation component took

to run, averaged per step.

## Using with GPU

We use the [Cudarc](https://github.com/coreylowman/cudarc) library for GPU (CUDA) integration. In the python binding, it

should be transparent.

We've exposed a slightly lower level API in rust, where you use setup a Stream and modules with Cudarc in your

application, and pass them to the library.

Rust setup example with Cudarc. Pass `dev`, defined below, to the `step` function.

```rust

let ctx = CudaContext::new(0).unwrap();

let stream = ctx.default_stream();

let dev = ComputationDevice::Gpu(GpuModules(stream);

```

To use with an Nvidia GPU, enable the `cuda` feature in `Cargo.toml`. The library will generate PTX instructions

as a publicly exposed string. Set up your application to use it from `dynamics::PTX`. It requires

CUDA 13 support, which requires Nvidia driver version 580 or higher.

## On unflattening trajactory data

If you passed multiple molecules, these will be flattened during runtime, and in snapshots. You

need to unflatten them if placing back into their original data structures.

## Why this when OpenMM exists?

This library exists as part of a larger Rust biology infrastructure effort. It's not possible to use

[OpenMM](https://openmm.org/) there due to the language barrier. This library currently only has a limited subset of the

functionality of OpenMM. It's unfortunate that, as a society, we've embraced a model of computing replete with

obstacles. In this case, the major

one is the one placed between programming languages.

While going around this obstacle, we attempt to jump over others, to make molecular dynamics more accessible.

This includes operating systems, software distribution, and user experience. We hope that this is easier to install and

use

than OpenMM; it can be used on any

Operating system, and any Python version >= 3.10, installable using `pip` or `cargo`.

This library is intended to *just work*. OpenMM does not natively work with molecules from online databases like RCSB

PDB,

PubChem, and Drugbank. It doesn't work with Amber GeoStd Mol2 files. OpenMM itself is easy to install with Pip, but the

additional libraries

it requires to load molecules and force fields are higher-friction. Getting a functional OpenMM configuration

for a given system involves work which we hope to eschew.

## Compiling from source

It requires these Amber parameter files to be present under the project's `resources` folder at compile time.

These are available in [Amber tools](https://ambermd.org/GetAmber.php). Download, unpack, then copy these files from

`dat/leap/parm` and `dat/leap/lib`:

- `amino19.lib`

- `aminoct12.lib`

- `aminont12.lib`

- `parm19.dat`

- `frcmod.ff19SB`

- `gaff2.dat`

- `ff-nucleic-OL24.lib`

- `ff-nucleic-OL24.frcmod`

- `RNA.lib`

We provide

a [copy of these files](https://github.com/David-OConnor/molchanicaa/releases/download/0.1.3/amber_params_sept_2025.zip)

for convenience; this is a much smaller download than the entire Amber package, and prevents needing to locate the

specific files.

Unpack, and place these under `resources` prior to compiling.

To build the Python library wheel, from the `python` subdirectory, run `maturin build`. You can load the library

locally for testing, once built, by running `pip install .`

## Eratta

- GPU operations are slower than they should, as we're passing all data between CPU and GPU each

time step.

- CPU SIMD unsupported

## References

- [Amber forcefields](https://ambermd.org/antechamber/gaff.html)

- [Amber reference manual](https://ambermd.org/doc12/Amber25.pdf)

- [Ewald Summation/SPME](https://manual.gromacs.org/nightly/reference-manual/functions/long-range-electrostatics.html)

- [OPC water model](https://arxiv.org/abs/1408.1679)

- [Tripos Mol2 format](https://zhanggroup.org/DockRMSD/mol2.pdf)