Bend in X minutes - the ultimate guide!

=======================================

Bend is a high-level, massively parallel programming language. That means it

feels like Python, but scales like CUDA. It runs on CPUs and GPUs, and you don't

have to do anything to make it parallel: as long as your code isn't "helplessly

sequential", it **will** use 1000's of threads!

While cool, Bend is far from perfect. In absolute terms it is still not so fast.

Compared to SOTA compilers like GCC or GHC, our code gen is still embarrassingly

bad, and there is a lot to improve. And, of course, in this beginning, there

will be tons of instability and bugs. That said, it does what it promises:

scaling horizontally with cores. And that's really cool! If you'd like to be an

early adopter of this interesting tech, this guide will teach you how to apply

Bend to build parallel programs in a new way!

For a more technical dive, check HVM2's

[paper](http://paper.HigherOrderCO.com/). For an entertaining, intuitive

explanation, see HVM1's classic

[HOW.md](https://github.com/HigherOrderCO/HVM/blob/master/guide/HOW.md). But if

you just want to dive straight into action - this guide is for you. Let's go!

Installation

------------

To use Bend, first, install [Rust nightly](https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/rust-programming-by/9781788390637/e07dc768-de29-482e-804b-0274b4bef418.xhtml). Then, install HVM2 and Bend itself with:

```

cargo +nightly install hvm

cargo +nightly install bend-lang

```

To test if it worked, type:

```

bend --help

```

For GPU support, you also need CUDA version `12.X`.

Hello, World!

-------------

As we said, Bend *feels* like Python - in some ways. It is high-level, you can

easily create objects and lists, there are ifs and loops. Yet, it is different:

there is some Haskell in it, in the sense algebraic datatypes, pattern-matching

and recursion play an important role. This is how its `"Hello, world!"` looks:

```python

def main():

return "Hello, world!"

```

Wait - there is something strange there. Why `return`, not `print`? Well, *for

now* (you'll read these words a lot), Bend doesn't have IO. We plan on

introducing it very soon! So, *for now*, all you can do is perform computations,

and see results. To run the program above, type:

```

bend run main.bend

```

If all goes well, you should see `"Hello, world!"`. The `bend run` command uses

the reference interpreter, which is slow. In a few moments, we'll teach you how

to run your code in parallel, on both CPUs and GPUs. For now, let's learn some

fundamentals!

Basic Functions and Datatypes

-----------------------------

In Bend, functions are pure: they receive something, and they return something.

That's all. Here is a function that tells you how old you are:

```python

def am_i_old(age):

if age < 18:

return "you're a kid"

else:

return "you're an adult"

def main():

return am_i_old(32)

```

That is simple enough, isn't it? Here is one that returns the distance between

two points:

```python

def distance(ax, ay, bx, by):

dx = bx - ax

dy = by - ay

return (dx * dx + dy * dy) ** 0.5

def main():

return distance(10.0, 10.0, 20.0, 20.0)

```

This isn't so pretty. Could we use tuples instead? Yes:

```python

def distance(a, b):

(ax, ay) = a

(bx, by) = b

dx = bx - ax

dy = by - ay

return (dx * dx + dy * dy) ** 0.5

def main():

return distance((10.0, 10.0), (20.0, 20.0))

```

So far, this does look like Python, doesn't it? What about objects? Well - here,

there is a difference. In Python, we have classes. In Bend, we just have the

objects themselves. This is how we create a 2D vector:

```python

object V2 { x, y }

def distance(a, b):

open V2: a

open V2: b

dx = b.x - a.x

dy = b.y - a.y

return (dx * dx + dy * dy) ** 0.5

def main():

return distance(V2 { x: 10.0, y: 10.0 }, V2 { x: 20.0, y: 20.0 })

```

This doesn't look too different, does it? What is that `open` thing, though? It

just tells Bend to *consume* the vector, `a`, "splitting" it into its

components, `a.x` and `a.y`. Is that really necessary? Actually, no - not

really. But, *for now*, it is. This has to do with the fact Bend is an affine

language, which... well, let's not get into that. For now, just remember we

need `open` to access fields.

Bend comes with 3 built-in numeric types: `u24`, `i24`, `f24`. That's quite

small, we admit. Soon, we'll have larger types. For now, that's what we got.

The `u24` type is written like `123` or `0xF`. The `i24` type requires a sign,

as in, `+7` or `-7`. The `f24` type uses `.`, like `3.14`.

Other than tuples, Bend has another, very general, way to encode data:

datatypes! These are just "objects with tags". A classic example of this is a

"shape", which can be either a circle or a rectangle. It is defined like this:

```python

type Shape:

Circle { radius }

Rectangle { width, height }

def area(shape):

match shape:

case Shape/Circle:

return 3.14 * shape.radius ** 2.0

case Shape/Rectangle:

return shape.width * shape.height

def main:

return area(Shape/Circle { radius: 10.0 })

```

In this example, `Shape` is a datatype with two variants: `Circle` and

`Rectangle`. The `area` function uses pattern matching to handle each variant

appropriately. Just like objects need `open`, datatypes need `match`, which

give us access to fields in each respective case.

Datatypes are very general. From matrices, to JSON, to quadtrees, every type of

data can be represented as a datatype (I mean, that's the name!). In fact,

lists - which, on Python, are actually stored as arrays - are represented using

datatypes on Bend. Specifically, the type:

```python

type List:

Nil

Cons { head, tail }

```

Here, the `Nil` variant represents an empty list, and the `Cons` variant

represents a concatenation between an element (`head`) and another list

(`tail`). That way, the `[1,2,3]` list could be written as:

```python

def main:

my_list = List/Cons { head: 1, tail: List/Cons { head: 2, tail: List/Cons { head: 3, tail: List/Nil }}}

return my_list

```

Obviously - that's terrible. So, you can write just instead:

```python

def main:

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

return my_list

```

Which is decent. But while it is written the same as in Python, it is important

to understand it is just the `List` datatype, which means we can operate on it

using the `match` notation. For example:

```python

def main:

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

match my_list:

case List/Cons:

return my_list.head

case List/Nil:

return 0

```

Will return `1`, which is the first element.

We also have a syntax sugar for strings in Bend, which is just a List of `u24`

characters (UTF-16 encoded). The `"Hello, world!"` type we've seen used it!

Bend also has inline functions, which work just like Python:

```python

def main:

mul_2 = lambda x: x * 2

return mul_2(7)

```

Except without the annoying syntax restrictions. You can also shorten it as `λ`,

if you can somehow type that.

*note - some types, like tuples, aren't being pretty-printed correctly after

computation. this will be fixed in the next days (TM)*

The Dreaded Immutability

------------------------

Finally, let's get straight to the fun part: how do we implement parallel

algorithms with Bend? Just kidding. Before we get there, let's talk about loops.

You might have noticed we have avoided them so far. That wasn't by accident.

There is an important aspect on which Bend diverges from Python, and aligns with

Haskell: **variables are immutable**. Not "by default". They just **are**. For

example, in Bend, we're not allowed to write:

```python

def parity(x):

result = "odd"

if x % 2 == 0:

result = "even"

return result

```

... because that would mutate the `result` variable. Instead, we should write:

```python

def is_even(x):

if x % 2 == 0:

return "even"

else:

return "odd"

def main:

return is_even(7)

```

Which is immutable. If that sounds annoying, that's because **it is**. Don't

let anyone tell you otherwise. We are aware of that, and we have many ideas on

how to improve this, making Bend feel even more Python-like. For now, we have to

live with it. But, wait... if variables are immutable... how do we even do

loops? For example:

```python

def sum(x):

total = 0

for i in range(10)

total += i

return total

```

Here, the entire way the algorithm works is by mutating the `total` variable.

Without mutability, loops don't make sense. The good news is Bend has *something

else* that is equally as - actually, more - powerful. And learning it is really

worth your time. Let's do it!

Folds and Bends

---------------

### Recursive Datatypes

Let's start by implementing a recursive datatype in Bend:

```python

type Tree:

Node { ~lft, ~rgt }

Leaf { val }

```

This defines a binary tree, with elements on leaves. For example, the tree:

```

__/\__

/\ /\

1 2 3 4

```

Could be represented as:

```

tree = Tree/Node {

lft: Tree/Node { lft: Tree/Leaf { val: 1 }, rgt: Tree/Leaf { val: 2 } },

rgt: Tree/Node { lft: Tree/Leaf { val: 3 }, rgt: Tree/Leaf { val: 4 } }

}

```

That's ugly. Very soon, we'll add a syntax sugar to make this shorter:

```

tree = ![![1,2],![3,4]]

```

As usual, for now, we'll live with the longer version.

### Fold: consuming recursive datatypes

Now, here's a question: how do we *sum* the elements of a tree? In Python, we

could just use a loop. In Bend, we don't have loops. Fortunately, there is

another construct we can use: it's called `fold`, and it works like a *search

and replace* for datatypes. For example, consider the code below:

```python

type Tree:

Node { ~lft, ~rgt }

Leaf { val }

def sum(tree):

fold tree:

case Tree/Node:

return tree.lft + tree.rgt

case Tree/Leaf:

return tree.val

def main:

tree = Tree/Node {

lft: Tree/Node { lft: Tree/Leaf { val: 1 }, rgt: Tree/Leaf { val: 2 } },

rgt: Tree/Node { lft: Tree/Leaf { val: 3 }, rgt: Tree/Leaf { val: 4 } }

}

return sum(tree)

```

It accomplishes the task by replacing every `Tree/Node { lft, rgt }` by `lft +

rgt`, and replacing every `Tree/Leaf` by `val`. As a result, the entire "tree of

values" is turned into a "tree of additions", and it evaluates as follows:

```python

nums = ((1 + 2) + (3 + 4))

nums = (3 + 7)

nums = 10

```

Now, this may look limiting, but it actually isn't. Folds are known for being

universal: *any algorithm that can be implemented with a loop, can be

implemented with a fold*. So, we can do much more than just compute an

"aggregated value". Suppose we wanted, for example, to transform every element

into a tuple of `(index,value)`, returning a new tree. Here's how to do it:

```python

type Tree:

Node { ~lft, ~rgt }

Leaf { val }

def enum(tree):

idx = 0

fold tree with idx:

case Tree/Node:

return Tree/Node {

lft: tree.lft(idx * 2 + 0),

rgt: tree.rgt(idx * 2 + 1),

}

case Tree/Leaf:

return (idx, tree.val)

def main:

tree = Tree/Node {

lft: Tree/Node { lft: Tree/Leaf { val: 1 }, rgt: Tree/Leaf { val: 2 }, },

rgt: Tree/Node { lft: Tree/Leaf { val: 3 }, rgt: Tree/Leaf { val: 4 }, }

}

return sum(tree)

```

Compared to the `sum` algorithm, 3 important things changed:

1. We initialize a state, `idx`, as `0`.

2. We pass new states down as `tree.xyz(new_idx)`

3. The base case receives the final state: the element index

So, in the end, we'll have computed a copy of the original tree, except that

every element has now became a tuple of index and value.

Now, please take a moment to think about this fact: **everything can be computed

with a fold.** This idea often takes some time to get used to, but, once you do,

it is really liberating, and will let you write better algorithms. As an

exercise, use `fold` to implement a "reverse" algorithm for lists:

```python

def reverse(list):

# exercise

?

def main:

return reverse([1,2,3])

```

## Bend: generating recursive datatypes

Bending is the opposite of folding. Whatever `fold` consumes, `bend` creates.

The idea is that, by defining an *initial state* and a *halting condition*, we

can "grow" a recursive structure, layer by layer, until the condition is met.

For example, consider the code below:

```python

type Tree:

Node { ~lft, ~rgt }

Leaf { val }

def main():

bend x = 0:

when x < 3:

tree = Tree/Node { lft: fork(x + 1), rgt: fork(x + 1) }

else:

tree = Tree/Leaf { val: 7 }

return tree

```

The program above will initialize a state (`x = 0`), and then, for as long as `x

< 3`, it will "fork" that state in two, creating a `Tree/Node`, and continuing

with `x + 1`. When `x >= 3`, it will halt and return a `Tree/Leaf` with `7`.

When all is done, the result will be assigned to the `tree` variable:

```python

tree = fork(0)

tree = ![fork(1), fork(1)]

tree = ![![fork(2),fork(2)], ![fork(2),fork(2)]]

tree = ![![![fork(3),fork(3)], ![fork(3),fork(3)]], ![![fork(3),fork(3)], ![fork(3),fork(3)]]]

tree = ![![![7,7], ![7,7]], ![![7,7], ![7,7]]]

```

With some imagination, we can easily see that, by recursively unrolling a state

this way, we can generate any structure we'd like. In fact, `bend` is so general

we can even use it to emulate a loop. For example, this Python program:

```python

sum = 0

idx = 0

while idx < 10:

sum = idx + sum

idx = idx + 1

```

Could be emulated in Bend with a "sequential bend":

```python

bend idx = 0:

when idx < 10:

sum = idx + fork(idx + 1)

else:

sum = 0

```

Of course, if you do it, Bend's devs will be very disappointed with you. Why?

Because everyone is here for one thing. Let's do it!

Parallel "Hello, World"

-----------------------

So, after all this learning, we're now ready to answer the ultimate question:

**How do we write parallel algorithms in Bend?**

At this point, you might have the idea: by using *folds* and *bends*, right?

Well... actually not! You do not need to use these constructs at all to make it

happen. Anything that *can* be parallelized *will* be parallelized on Bend. To

be more precise, this:

```

f(g(x))

```

Can NOT be parallelized, because `f` **depends** on the result of `g`. But this:

```

H(f(x), g(y))

```

Can be parallelized, because `f(x)` and `g(y)` are **independent**. Traditional

loops, on the other hands, are inherently sequential. A loop like:

```python

sum = 0

for i in range(8):

sum += i

```

Is actually just a similar way to write:

```python

sum = (0 + (1 + (2 + (3 + (4 + (5 + (6 + 7)))))))

```

Which is *really bad* for parallelism, because the only way to compute this is

by evaluating the expressions one after the other, in order:

```python

sum = (0 + (1 + (2 + (3 + (4 + (5 + (6 + 7)))))))

sum = (0 + (1 + (2 + (3 + (4 + (5 + 13))))))

sum = (0 + (1 + (2 + (3 + (4 + 18)))))

sum = (0 + (1 + (2 + (3 + 22))))

sum = (0 + (1 + (2 + 25)))

sum = (0 + (1 + 27))

sum = (0 + 28)

sum = 28

```

There is nothing Bend could do to save this program: sequentialism is an

inherent part of its logic. Now, if we had written, instead:

```python

sum = (((0 + 1) + (2 + 3)) + ((4 + 5) + (6 + 7)))

```

Then, we'd have a much easier time evaluating that in parallel. Look at it:

```python

sum = (((0 + 1) + (2 + 3)) + ((4 + 5) + (6 + 7)))

sum = ((1 + 5) + (9 + 13))

sum = (6 + 22)

sum = 28

```

That's so much better that even the *line count* is shorter!

So, how do you write a parallel program in Bend?

**Just write algorithms that aren't helplessly sequential.**

That's all there is to it. As long as you write programs like that one, then

unlike the former one, they will run in parallel. And that's why `bend` and

`fold` are core features: they're, essentially, parallelizable loops. For

example, to add numbers in parallel, we can write:

```python

def main():

bend d = 0, i = 0:

when d < 28:

sum = fork(d+1, i*2+0) + fork(d+1, i*2+1)

else:

sum = i

return sum

```

And that's the parallel "Hello, world"! Now, let's finally run it. But first,

let's measure its single-core performance. Also, remember that, for now, Bend

only supports 24-bit numbers (`u24`), thus, the results will always be in `mod

16777216`.

```

bend run main.bend

```

On my machine (Apple M3 Max), it completes after `147s`, at `65 MIPS` (Million

Interactions Per Second - Bend's version of the FLOPS). That's too long. Let's

run it in parallel, by using the **C interpreter** instead:

```

bend run-c main.bend

```

And, just like that, the same program now runs in `8.49s`, at `1137 MIPS`.

That's **18x faster**! Can we do better? Sure: let's use the **C compiler** now:

```

bend gen-c main.bend >> main.c

```

This command converts your `bend` file into a small, dependency-free C file

that does the same computation much faster. You can compile it to an executable:

```

gcc main.c -o main -O2 -lm -lpthread # if you're on Linux

gcc main.c -o main -O2 # if you're on OSX

./main

```

Now, the same program runs in `5.81s`, at `1661.91 MIPS`. That's now **25x

faster** than the original! Can we do better? Let's now enter the unexplored

realms of arbitrary high-level programs on... GPUs. How hard that could be?

Well, for us... it was. A lot. For you... just call the **CUDA interpreter**:

```

bend run-cu main.bend

```

And, simply as that, the same program now runs in `0.82s`, at a blistering

`11803.24 MIPS`. That's **181x faster** than the original. Congratulations!

You're now a thread bender.

~

As a last note, you may have noticed that the compiled version isn't much faster

than the interpreted one. Our compiler is still on its infancy, and the assembly

generated is quite abysmal. Most of our effort went into setting up a foundation

for the parallel evaluator, which was no easy task. With that out of our way,

improving the compiler is a higher priority now. You can expect it to improve

continuously over time. For now, it is important to understand the state of

things, and set up reasonable expectations.

A Parallel Bitonic Sort

-----------------------

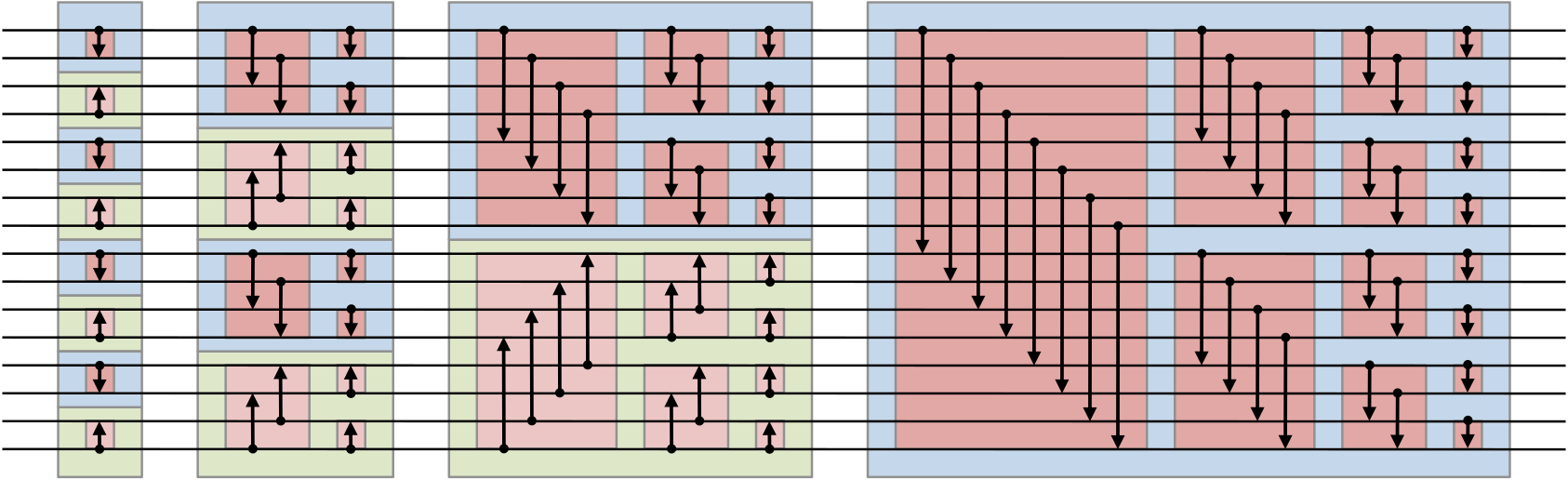

The bitonic sort is a popular algorithm that sorts a set of numbers by moving

them through a "circuit" (sorting network) and swapping as they pass through:

In CUDA, this can be implemented by using mutable arrays and synchronization

primitives. This is well known. What is less known is that it can also be

implemented as a series of *immutable tree rotations*, with pattern-matching and

recursion. Don't bother trying to understand it, but, here's the code:

```python

def gen(d, x):

switch d:

case 0:

return x

case _:

return (gen(d-1, x * 2 + 1), gen(d-1, x * 2))

def sum(d, t):

switch d:

case 0:

return t

case _:

(t.a, t.b) = t

return sum(d-1, t.a) + sum(d-1, t.b)

def swap(s, a, b):

switch s:

case 0:

return (a,b)

case _:

return (b,a)

def warp(d, s, a, b):

switch d:

case 0:

return swap(s + (a > b), a, b)

case _:

(a.a,a.b) = a

(b.a,b.b) = b

(A.a,A.b) = warp(d-1, s, a.a, b.a)

(B.a,B.b) = warp(d-1, s, a.b, b.b)

return ((A.a,B.a),(A.b,B.b))

def flow(d, s, t):

switch d:

case 0:

return t

case _:

(t.a, t.b) = t

return down(d, s, warp(d-1, s, t.a, t.b))

def down(d,s,t):

switch d:

case 0:

return t

case _:

(t.a, t.b) = t

return (flow(d-1, s, t.a), flow(d-1, s, t.b))

def sort(d, s, t):

switch d:

case 0:

return t

case _:

(t.a, t.b) = t

return flow(d, s, sort(d-1, 0, t.a), sort(d-1, 1, t.b))

def main:

return sum(18, sort(18, 0, gen(18, 0)))

```

As a test of Bend's ability to parallelize the most insanely high-level

computations possible, let's benchmark this program. Here are the results:

- 12.33s / 102 MIPS (Apple M3 Max, 1 thread)

- 0.96s / 1315 MIPS (Apple M3 Max, 16 threads) - 12x speedup

- 0.24s / 5334 MIPS (NVIDIA RTX 4090, 16k threads) - 51x speedup

And, just like magic, it works! 51x faster on RTX. How cool is that?

Of course, you would absolutely **not** want to sort numbers like that,

specially when mutable arrays exist. But there are many algorithms that *can

not* be implemented easily with buffers. Evolutionary and genetic algorithms,

proof checkers, compilers, interpreters. For the first time ever, you can

implement these algorithms as high-level functions, in a language that runs on

GPUs. That's the magic of Bend!

Graphics Rendering

------------------

While the algorithm above does parallelize well, it is very memory-hungry. It is

a nice demo of Bend's potential, but isn't a great way to sort lists. Currently,

Bend has a 4GB memory limit (for being a 32-bit architecture). When the memory

is filled, its performance will degrade considerably. But we can do better.

Since Bend is GC-free, we can express low memory footprint programs using `bend`

or tail calls. For maximum possible performance, one should first create enough

"parallel room" to fill all available cores, and then spend some time doing

compute-heavy, but less memory-hungry, computations. For example, consider:

```python

# given a shader, returns a square image

def render(depth, shader):

bend d = 0, i = 0:

when d < depth:

color = (fork(d+1, i*2+0), fork(d+1, i*2+1))

else:

width = depth / 2

color = demo_shader(i % width, i / width)

return color

# given a position, returns a color

# for this demo, it just busy loops

def demo_shader(x, y):

bend i = 0:

when i < 100000:

color = fork(i + 1)

else:

color = 0x000001

return color

# renders a 256x256 image using demo_shader

def main:

return render(16, demo_shader)

```

It emulates an OpenGL fragment shader by building an "image" as a perfect binary

tree, and then calling the `demo_shader` function on each pixel. Since the tree

has a depth of 16, we have `2^16 = 65536 pixels`, which is enough to fill all

cores of an RTX 4090. Moreover, since `demo_shader` isn't doing many

allocations, it can operate entirely inside the GPU's "shared memory" (L1

cache). Each GPU thread has a local space of 64 IC nodes. Functions that don't

need more than that, like `demo_shader`, can run up to 5x faster!

On my GPU, it performs `22,000 MIPS` out of the box, and `40000+ MIPS` with a

tweak on the generated CUDA file (doubling the `TPC`, which doubles the number

of threads per block). In the near future, we plan to add immutable textures,

allowing for single-interaction sampling. With some napkin math, this should be

enough to render 3D games in real-time. Imagine a future where game engines are

written in Python-like languages? That's the future we're building, with Bend!

To be continued...

------------------

This guide isn't extensive, and there's a lot uncovered. For example, Bend also

has an entire "secret" Haskell-like syntax that is compatible with old HVM1.

[Here](https://gist.github.com/VictorTaelin/9cbb43e2b1f39006bae01238f99ff224) is

an implementation of the Bitonic Sort with Haskell-like equations. We'll

document its syntax here soon!

Community

---------

Remember: Bend is very new and experimental. Bugs and imperfections should be

expected. That said, [HOC](https://HigherOrderCO.com/) will provide long-term

support to Bend (and its runtime, HVM2). So, if you believe this paradigm will

be big someday, and want to be part of it in these early stages, join us on

[Discord](https://Discord.HigherOrderCO.com/). Report bugs, bring your

suggestions, and let's chat and build this future together!