1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237

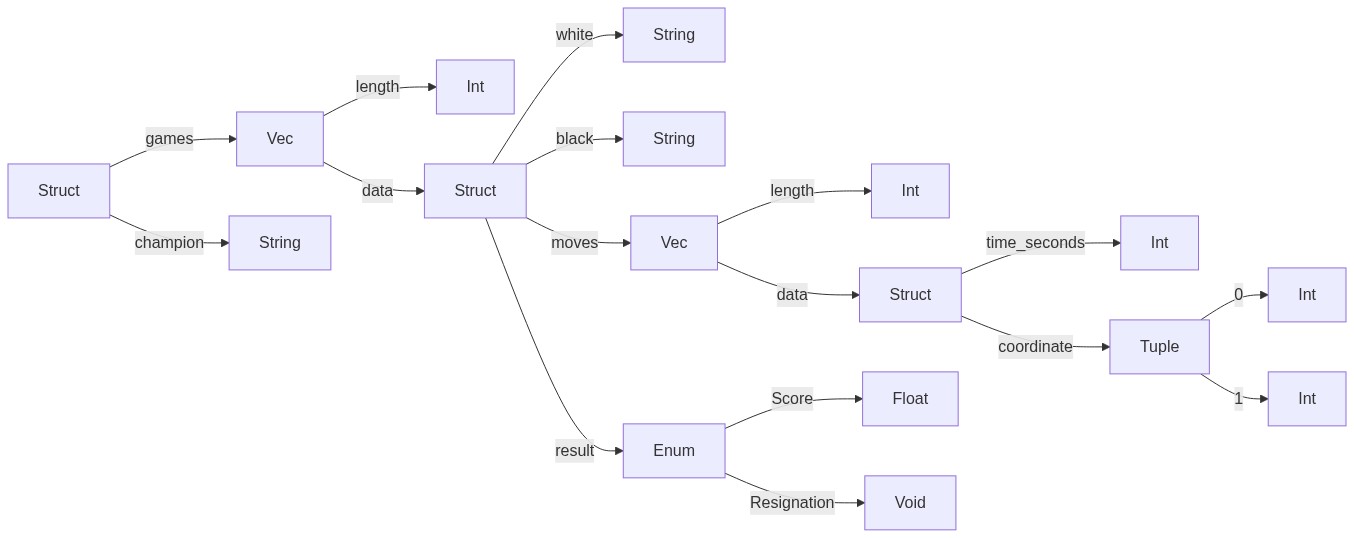

//! # What's Tree-buf? //! Tree-buf is an efficient serialization system built for real-world data sets and applications. //! //! It's key features are: //! * Compact representation //! * Very fast encode and decoding //! * Flexible schemas //! * Backwards and forwards compatibility //! * Self-describing //! * Easy to use //! * Application-defined partial parsing and schema matching //! //! Tree-buf is built for scale. Its data layout enables the use of SIMD accellerated, bit-packed compression techniques under the hood. //! //! ## Warning! //! Tree-buf is in early development and the format is changing rapidly. It may not be a good idea to use Tree-buf in production. If you do, make sure you test a lot and be prepared to do data migrations on every major release of the format. I take no responsibility for your poor choice of using Tree-buf. //! //! # Getting started with Tree-buf //! //! While the Tree-buf format is language agnostic, it is currently only available for Rust. //! //! __Step 1__: Add the latest version tree-buf to your `cargo.toml` //! ```toml //! [dependencies] //! tree-buf = "0.5.0" //! ``` //! //! __Step 2__: Derive `Read` and / or `Write` on your structs. //! //! ```ignore //! use tree_buf::prelude::*; //! //! #[derive(Read, Write, PartialEq)] //! pub struct Data { //! pub id: u32, //! pub vertices: Vec<(f64, f64, f64)>, //! pub extra: Option<String>, //! } //! ``` //! //! __Step 3__: Call `read` and / or `write` on your data. //! //! ```ignore //! pub fn round_trip() { //! // Make some data //! let data = Data { //! id: 1, //! vertices: vec! [ //! (10., 10., 10.), //! (20., 20., 20.) //! ], //! extra: String::from("Fast"), //! }; //! // Write to Vec<u8> //! let bytes = write(&data); //! // Read from &[u8] //! let copy = read(&bytes).unwrap(); //! // Success! //! assert_eq!(©, &data); //! } //! ``` //! //! Done! You have mastered the use of Tree-buf. //! //! # Tree-buf under the hood //! How does Tree-buf enable fast compression and serialization of real-world data? //! //! 1. Organize the document into a tree/branches data model which clusters related data together. //! 2. Use best-in-breed compression that is only available to typed vectors of primitive data. //! 3. Amortize the cost of the self-describing schema. //! //! To break these down concretely, it will be useful to track an example using real-world data. We'll take a look at the data, see how maps to the Tree-buf data model, and then see how Tree-buf applies compression to each part of the resulting model. //! //! Let's say that we want to store all of the game records for a round-robin tournament of Go. To follow along, you won't need any knowledge of the game. Suffice to say that it's played on a 19x19 grid and players alternate placing white and black stones on the intersections of the board. It looks like this: //! //!  //! //! Here is what a simplified schema might look like for those recorded games. //! //! ```rust //! struct Tournament { //! games: Vec<Game>, //! champion: String, //! } //! //! struct Game { //! white: String, //! black: String, //! moves: Vec<Move>, //! result: Result, //! } //! //! struct Move { //! time_seconds: u32, //! coordinate: (u8, u8), //! } //! //! enum Result { //! Score(f32), //! Resignation(String), //! } //! ``` //! //! And some sample data in that schema, given in `json`... //! //! ```json //! { //! "champion": "Lee Changho", //! "games": [ //! { //! "white": "Honinbo Shusai", //! "black": "Go Seigen", //! "moves": [ //! { //! "time_seconds": 4, //! "coordinate": [16, 2], //! }, //! { //! "time_seconds": 9, //! "coordinate": [2, 3], //! }, //! /* Followed by 246 more moves from the first game */ //! ], //! "result": 1.5, //! }, //! /* Followed by 119 more games from the tournament */ //! ] //! } //! ``` //! //! ## The Tree-buf data model //! //! Tree-buf considers each path from the root through the schema as it's own branch of a tree. //! //! Here is an illustration of what that breakdown would look like for our schema: //! //!  //! //! //! Each branch in the tree stores contains all of the primitives accessible at that path through the schema, in the order that it occurs in the data. //! //! For example, there is an `Int` branch that exists at `->games->data->moves->data->time_seconds`. This branch would store all of the time samples for all moves for all games throughout the tournament. Eg: `[4, 9, ... 246 more time samples from the first game, ... time samples from the second game through the last game]`. //! //! Similarly, the x-coordinate of all the moves from all the games though the path `->games->data->moves->data->coordinate->0` are stored contiguously: `[16, 2, ... and so on]` //! //! Not all data ends up in a `Vec`. For example, there is only one possible `String` through the branch `->champion`. Data inside a `Vec` may be encoded differently then data outside a `Vec`. //! //! ## Compressing the Tree-buf model //! //! >Real-world data exhibits patterns. If your data does not exhibit some sort of pattern it's probably not very interesting. //! //! The Tree-buf data model clusters related data together so that it can take advantage of the patterns in your data using highly optimized compression libraries. //! //! For example, values in the `time_seconds` field aren't random. They are monotonically increasing, and usually at a regular rate since games tend to proceed forward in a rhythm, with the occasional slowdown. The integer compression in Tree-buf can take advantage of this. By utilizing, for example, delta encoding + Simple16, values can be represented usually in less than a single byte. //! //! Similarly, `coordinate`s in Go games aren't really random either. A move in Go is very likely to be in the same quadrant of the board as the previous move, if not adjacent to it. Again, utilizing for example delta encoding + Simple16 can get a series of adjacent moves down to about 2 bits per coordinate component, or about 3 bits per coordinate component for a series of moves within a quadrant. It is crucial here that the Tree-buf data model has split up the `x` and `y` coordinates into their own branch, because these values cluster independently of each other. If these values were interleaved, they would appear more random to an integer compression library. //! //! Even the names of the players aren't random. Because a round-robin tournament between 16 players requires 120 matches, the names of the players are highly redundant. Here too, we can keep track of which `Strings` have been written recently and simply refer to previous strings within a given list. //! //! Add these to first class support for enums, tuples, nullables, and a few other tricks and it adds up to significant wins. //! //! >All of this compression in Tree-buf happens behind the scenes, without any work on the part of the developer, and without any modification to the schema. //! //! ## Comparison of compression results to other formats //! Let's compare these results to another popular binary format, `Protobuf 3` to see what a difference the accumulation of many small wins makes. For now, let's just consider the moves vector since that's the largest portion of the data. Each move in `Protobuf` is it's own message. Each message in protobuf is length delimited, requiring 1 byte. After the first 2 minutes and 7 seconds of the game clock, each `time_seconds` will require 2 bytes for the `LEB128` encoded value and 1 byte for the field id - 3 bytes. For the coordinate field we can cheat and implement this using a packed array. That doesn't exactly match the data model, but would require fewer bytes than an embedded message. A packed array requires 1 byte for the field id, 1 byte for the length prefix, and 1 byte each for the two values. Add these together, and you get 7 bytes per move, or 56 bits. //! //! Depending on the game, Tree-buf may require on average only 14 bits per move. ~3 bits each for the coordinate deltas, plus ~8 bits or less for time deltas of up to 2 minutes, 7 seconds. That is to say, __the moves list will require about 4 times as much space in `Protobuf 3` as compared to `Tree-buf`__ (14 bits * 4 = 56 bits). //! //! As compared to `json`? With 14 bits per move we can get... `"t`. Actually that went over budget a bit and took 16 bits. Didn't quite make it as far as `"time_seconds":`. The complete, minified move will require a whopping 336 bits, 24 times as much as `Tree-buf`. //! //! # Other tricks //! //! Because the data model separates data by path down the schema, it becomes easy to selectively load parts of the file without requiring loading, parsing, and de-compressing data we aren't interested in. //! //! Continuing with the Go tournament example, if we wanted to just collect the results of the game and not the moves vector we could just modify the struct that we pass to `read` by removing the fields we don't need. Tree-buf will then only parse as much of the file as is necessary to match the schema. pub mod internal; pub mod prelude { // Likely the minimum API that should go here. It's easier to add later than to remove. pub use { crate:: { read, write }, tree_buf_macros:: { Read, Write } }; // This section makes everything interesting available to the rest of the crate // without bothering to manage imports. pub(crate) use crate::{internal::*, error::*, primitive::{Primitive, PrimitiveId} }; pub(crate) type ReadResult<T> = Result<T, ReadError>; } pub use prelude::*; pub use internal::error::ReadError; // TODO: Create another Readable/Writable trait that would be public, without the associated type. Then impl Readable for the internal type. // That would turn Readable into a tag that one could use as a constraint, without exposing any internal details pub use internal::{Readable, Writable, NonArrayBranch}; use internal::encodings::varint::{encode_suffix_varint}; pub fn write<'a, 'b: 'a, T: Writable<'a>>(value: &'b T) -> Vec<u8> { let mut writer = T::Writer::default(); writer.write(value); let mut lens = Vec::new(); let mut bytes = Vec::new(); // TODO: The pre-amble could come back as optional, as long as it has it's own PrimitiveId writer.flush(NonArrayBranch, &mut bytes, &mut lens); for len in lens.iter().rev() { encode_suffix_varint(*len as u64, &mut bytes); } bytes } pub fn read<T: Readable>(bytes: &[u8]) -> ReadResult<T> { let sticks = read_root(bytes)?; let mut reader = T::Reader::new(sticks, NonArrayBranch)?; reader.read() } // TODO: Figure out recursion, at least enough to handle this: https://docs.rs/serde_json/1.0.44/serde_json/value/enum.Value.html // TODO: Nullable should be able to handle recursion as well, even if Option doesn't. (Option<Box<T>> could though) // TODO: When deriving, use the assert implements check that eg: Clone does, to give good compiler errors // If this is not possible because it's an internal API, use static_assert // TODO: Evaluate TurboPFor https://github.com/powturbo/TurboPFor // or consider the best parts of it. The core differentiator here // is the ability to use this.