1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248

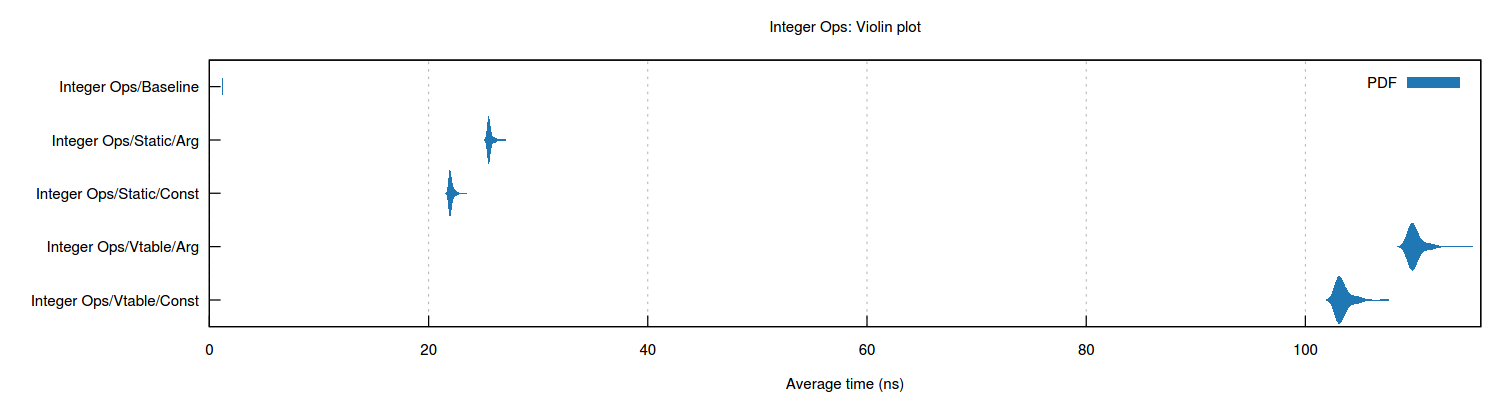

#![macro_use] /*! Zero_V is an experiment in defining behavior over collections of objects implementing some trait without dynamic polymorphism. This is a small crate with some helper utilities, along with the zero_v macro which generates the boilerplate necessary for your traits and functions to support the collections generated by Zero_V. It can be useful if all of the following are true: * Library users will always know the composition of the collection of types at compile time. * Library users should be able to alter collection composition easily. * Vtable overhead matters. For example, lets imagine you've written an event logging library that allows users to extend it with plugins to alter events before logging. Using dynamic polymorphism/ vtables, client code might look something like: ```ignore let plugins: Vec<Box<dyn Plugin>> = Vec![ Box::new(TimestampReformatter::new()), Box::new(HostMachineFieldAdder::new()), Box::new(UserFieldAdder::new()), ]; let mut logger = EventLogger::with_plugins(plugins); let events = EventStream::new(); for event in events.listen() {logger.log_event(event)}; ``` This is a fine way to approach the problem in most cases. It's easy for clients to set up and you rarely care about the overhead of the virtual calls. But if you do care about overhead, a Zero_V version of the above looks like: ```ignore use zero_v::{compose, compose_nodes}; let plugins = compose!( TimestampReformatter::new(), HostMachineFieldAdder::new(), UserFieldAdder::new() ); let mut logger = EventLogger::with_plugins(plugins); let events = EventStream::new(); for event in events.listen() {logger.log_event(event)}; ``` To the client the only real difference here is the use of the compose macro, dropping the boxing for each plugin in the collection and the extra Zero_V imports. But internally, your type is now generic over a type defined without the use of boxing or vtables, which encourages the compiler to monomorphise the plugin use and remove the virtual function calls. # Adding zero_v to your project To add zero_v to your project, add the following to your Cargo.toml under dependencies ```ignore [dependencies] zero_v = "0.2.0" ``` If you're an end-user who just needs to create a collection, or you want to implement the boilerplate for your trait yourself (not recommended if you can avoid it, but you may need to if your trait involves generics or references as arguments) then you can use the crate without the zero_v attribute macro with: ```ignore [dependencies] zero_v = { version = "0.2.0", default-features = false } ``` # Implementing Zero_V for your type with the zero_v macro If your trait doesn't involve arguments with lifetimes or generics then the zero_v macro gives you all of your boilerplate for free. All you need to do is drop it on top of your trait definition: ``` use zero_v::{zero_v}; // The trait_types argument tells the macro to generate all the traits you'll // need for iteration over a collection of items implementing your trait. #[zero_v(trait_types)] trait IntOp { fn execute(&self, input: usize) -> usize; } // Passing the fn_generics arguments to the macro tells it to produce proper // generic bounds for the second argument. The second argument takes the form // <X> as <Y> where <X> is the name of your trait and <Y> is the name you're // giving to the generic parameter which can accept a zero_v collection. #[zero_v(fn_generics, IntOp as IntOps)] fn sum_map(input: usize, ops: &IntOps) -> usize { ops.iter_execute(input).sum() } ``` # Implementing Zero_V for your type manually To enable Zero_V, you'll need to add a pretty large chunk of boilerplate to your library. This code walks you through it step by step for a simple example. ``` use zero_v::{Composite, NextNode, Node}; // This is the trait we want members of client collections to implement. trait IntOp { fn execute(&self, input: usize) -> usize; } // First, you'll need a level execution trait. It will have one method // which extends the signature of your trait's core function with an extra // paremeter of type usize (called level here) and wraps the output in an // option (these changes will allow us to return the outputs of the function // from an iterator over the collection. trait IntOpAtLevel { fn execute_at_level(&self, input: usize, level: usize) -> Option<usize>; } // You'll need to implement this level execution trait for two types, // The first type is Node<A, B> where A implements your basic trait and B // implements the level execution trait. For this type, just // copy the body of the function below, updating the contents of the if/else // blocks with the signature of your trait's function. impl<A: IntOp, B: NextNode + IntOpAtLevel> IntOpAtLevel for Node<A, B> { fn execute_at_level(&self, input: usize, level: usize) -> Option<usize> { if level == 0 { Some(self.data.execute(input)) } else { self.next.execute_at_level(input, level - 1) } } } // The second type is the unit type. For this implementation, just return None. impl IntOpAtLevel for () { fn execute_at_level(&self, _input: usize, _level: usize) -> Option<usize> { None } } // Next you'll need to create an iterator type for collections implementing // your trait. The iterator will have one field for each argument to your // trait's function, along with a level field and a parent reference to // a type implementing your level execution trait and NextNode. struct CompositeIterator<'a, Nodes: NextNode + IntOpAtLevel> { level: usize, input: usize, parent: &'a Nodes, } // Giving your iterator a constructor is optional. impl<'a, Nodes: NextNode + IntOpAtLevel> CompositeIterator<'a, Nodes> { fn new(parent: &'a Nodes, input: usize) -> Self { Self { parent, input, level: 0, } } } // You'll need to implement Iterator for the iterator you just defined. // The item type will be the return type of your function. For next, just // copy the body of next below, replacing execute_at_level with the // signature of your execute_at_level function. impl<'a, Nodes: NextNode + IntOpAtLevel> Iterator for CompositeIterator<'a, Nodes> { type Item = usize; fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item> { let result = self.parent.execute_at_level(self.input, self.level); self.level += 1; result } } // Almost done. Now you'll need to define a trait returning your iterator // type. trait IterExecute<Nodes: NextNode + IntOpAtLevel> { fn iter_execute(&self, input: usize) -> CompositeIterator<'_, Nodes>; } // Finally, implement your iterator return trait on a composite over Nodes // bound by NextNode and your level execution trait which returns // your iterator. impl<Nodes: NextNode + IntOpAtLevel>IterExecute<Nodes> for Composite<Nodes> { fn iter_execute(&self, input: usize) -> CompositeIterator<'_, Nodes> { CompositeIterator::new(&self.head, input) } } ``` # Benchmarks Some example benchmarks for Zero_V are captured below. The source takes two sets of objects implementing a simple trait transforming a usize to another usize, (one taking a constructor argument and one using a small extra const optimization), and then implements the benchmark with one dynamic collection (the standard vtable way) and one static collection (using Zero_V) for each of those sets. Results are given below (Hardware was a Lenovo T430 and benchmarks were compiled using rustc 1.52.1, so your mileage may vary)  Zero_V comes out of this benchmark looking pretty good, but I do want to stress the following caveats. * This was using a trait where each iteration of the loop did a very small amount of work (a single multiplication, addition, rshift or lshift op). Basically this means that these benchmarks should make Zero_V look as good as it will ever look, since the vtable overhead will be as large as possible relative to the amount of work per iteration. * Every use case is different, every machine is different and compilers can be fickle. If performance is important enough to pay the structural costs this technique will impose on your code, it's probably important enough to verify you're getting the expected speedups by running your own benchmark suite, and making sure those benchmarks are reflected in production. The benchmarks above also make aggressive use of inline annotations for trait implementations, and removing a single annotation can make the execution three times slower, so it's can be worth exploring inlining for your own use case (dependent on your performance needs). * The eagle-eyed amongst you might notice there's a fifth benchmark, baseline, that completes in a little over a nanosecond. This is the version of the benchmarks that dispenses with traits and objects and just has a single function which performs the work we're doing in the other benchmarks (execute a set of integer ops on our input and sum the outputs). Depending on your use case, it might be a good idea to design your APIs so that anyone who wants to hardcode an optimized solution like that has the tools to do so. If you're good to your compiler, your compiler will be good to you (occasional compiler bugs notwithstanding). */ mod composite; #[cfg(test)] mod test; pub use composite::{Composite, NextNode, Node}; #[cfg(feature = "gen")] extern crate zero_v_gen; #[cfg(feature = "gen")] pub use zero_v_gen::zero_v;