1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288 289 290 291 292 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368 369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 491 492 493 494 495 496 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505 506 507 508 509 510 511 512 513 514 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 542 543 544 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552 553 554 555 556 557 558 559 560 561 562 563 564 565 566 567 568 569 570 571 572 573 574 575 576 577 578 579 580 581 582 583 584 585 586 587 588 589 590 591 592 593 594 595 596 597 598 599 600 601 602 603 604 605 606 607 608 609 610 611 612 613 614 615 616 617 618 619 620 621 622 623 624 625 626 627 628 629 630 631 632 633 634

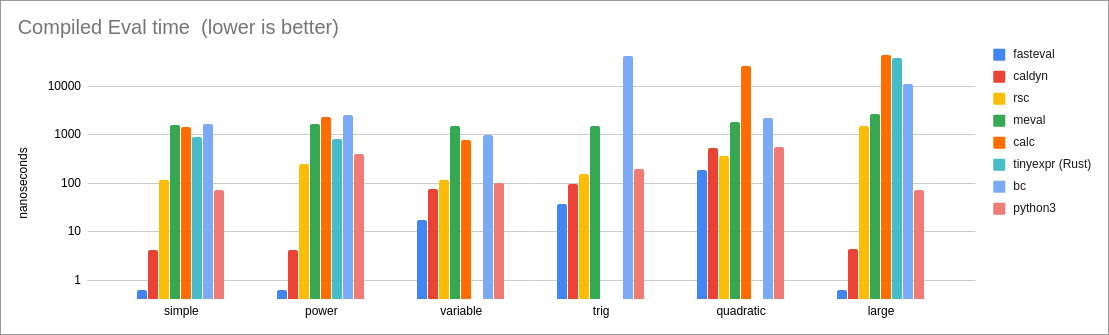

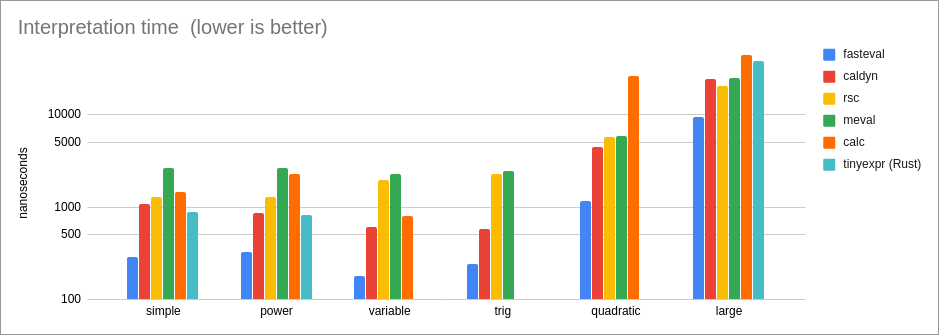

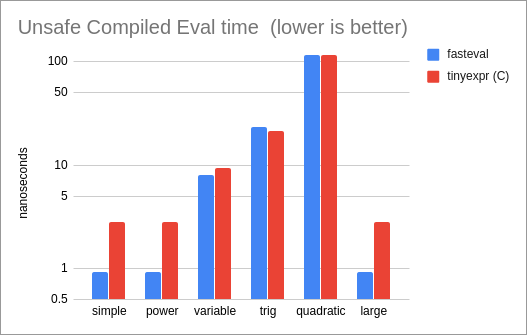

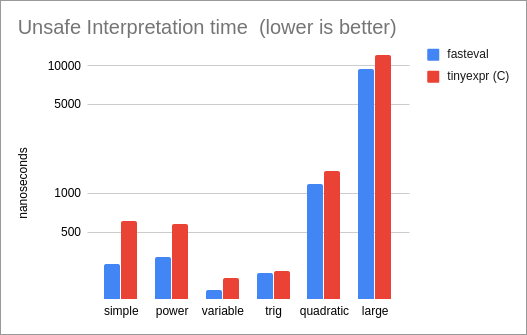

//! Fast evaluation of algebraic expressions //! //! # Features //! * No dependencies. //! * Safe execution of untrusted expressions. //! * Works with stable Rust. //! * Supports interpretation (i.e. parse & eval) as well as compiled execution (i.e. parse, compile, eval). //! * Supports Variables and Custom Functions. //! * `fasteval` is a good base for building higher-level languages. //! * Supports many built-in functions and constants. //! * Supports all the standard algebraic unary and binary operators (+ - * / ^ %), //! as well as comparisons (< <= == != >= >) and logical operators (&& ||) with //! short-circuit support. //! * Easy integration into many different types of applications, including scoped evaluation. //! * Very fast performance. //! //! # The `fasteval` Expression "Mini-Language" //! //! ## Built-in Functions and Constants //! //! These are the built-in functions that `fasteval` expressions support. (You //! can also add your own custom functions and variables -- see the //! [Examples](#advanced-variables-and-custom-functions) section.) //! //! ```text //! * print(...strings and values...) -- Prints to stderr. Very useful to 'probe' an expression. //! Evaluates to the last value. //! Example: `print("x is", x, "and y is", y)` //! Example: `x + print("y:", y) + z == x+y+z` //! //! * log(base=10, val) -- Logarithm with optional 'base' as first argument. //! If not provided, 'base' defaults to '10'. //! Example: `log(100) + log(e(), 100)` //! //! * e() -- Euler's number (2.718281828459045) //! * pi() -- π (3.141592653589793) //! //! * int(val) //! * ceil(val) //! * floor(val) //! * round(modulus=1, val) -- Round with optional 'modulus' as first argument. //! Example: `round(1.23456) == 1 && round(0.001, 1.23456) == 1.235` //! //! * abs(val) //! * sign(val) //! //! * min(val, ...) -- Example: `min(1, -2, 3, -4) == -4` //! * max(val, ...) -- Example: `max(1, -2, 3, -4) == 3` //! //! * sin(radians) * asin(val) //! * cos(radians) * acos(val) //! * tan(radians) * atan(val) //! * sinh(val) * asinh(val) //! * cosh(val) * acosh(val) //! * tanh(val) * atanh(val) //! ``` //! //! ## Operators //! //! The `and` and `or` operators are enabled by default, but if your //! application wants to use those words for something else, they can be //! disabled by turning off the `alpha-keywords` feature (`cargo build --no-default-features`). //! //! ```text //! Listed in order of precedence: //! //! (Highest Precedence) ^ Exponentiation //! % Modulo //! / Division //! * Multiplication //! - Subtraction //! + Addition //! == != < <= >= > Comparisons (all have equal precedence) //! && and Logical AND with short-circuit //! (Lowest Precedence) || or Logical OR with short-circuit //! //! ``` //! //! ## Numeric Literals //! //! ```text //! Several numeric formats are supported: //! //! Integers: 1, 2, 10, 100, 1001 //! //! Decimals: 1.0, 1.23456, 0.000001 //! //! Exponents: 1e3, 1E3, 1e-3, 1E-3, 1.2345e100 //! //! Suffix: //! 1.23p = 0.00000000000123 //! 1.23n = 0.00000000123 //! 1.23µ, 1.23u = 0.00000123 //! 1.23m = 0.00123 //! 1.23K, 1.23k = 1230 //! 1.23M = 1230000 //! 1.23G = 1230000000 //! 1.23T = 1230000000000 //! ``` //! //! # Examples //! //! ## Easy evaluation //! The [`ez_eval()`](ez/fn.ez_eval.html) function performs the entire allocation-parse-eval process //! for you. It is slightly inefficient because it always allocates a //! fresh [`Slab`](slab/index.html), but it is very simple to use: //! //! ``` //! // In case you didn't know, Rust allows `main()` to return a `Result`. //! // This lets us use the `?` operator inside of `main()`. Very convenient! //! fn main() -> Result<(), fasteval::Error> { //! // This example doesn't use any variables, so just use an EmptyNamespace: //! let mut ns = fasteval::EmptyNamespace; //! //! let val = fasteval::ez_eval( //! "1+2*3/4^5%6 + log(100K) + log(e(),100) + [3*(3-3)/3] + (2<3) && 1.23", &mut ns)?; //! // | | | | | | | | //! // | | | | | | | boolean logic with short-circuit support //! // | | | | | | comparisons //! // | | | | | square-brackets act like parenthesis //! // | | | | built-in constants: e(), pi() //! // | | | 'log' can take an optional first 'base' argument, defaults to 10 //! // | | numeric literal with suffix: p, n, µ, m, K, M, G, T //! // | many built-in functions: print, int, ceil, floor, abs, sign, log, round, min, max, sin, asin, ... //! // standard binary operators //! //! assert_eq!(val, 1.23); //! //! Ok(()) //! } //! ``` //! //! //! ## Simple variables //! Several namespace types are supported, each designed for different situations. //! ([See the various Namespace types here.](evalns/index.html)) For simple cases, you can define variables with a //! [`BTreeMap`](https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/collections/struct.BTreeMap.html): //! //! ``` //! use std::collections::BTreeMap; //! fn main() -> Result<(), fasteval::Error> { //! let mut map : BTreeMap<String,f64> = BTreeMap::new(); //! map.insert("x".to_string(), 1.0); //! map.insert("y".to_string(), 2.0); //! map.insert("z".to_string(), 3.0); //! //! let val = fasteval::ez_eval(r#"x + print("y:",y) + z"#, &mut map)?; //! // | //! // prints "y: 2" to stderr and then evaluates to 2.0 //! //! assert_eq!(val, 6.0); //! //! Ok(()) //! } //! ``` //! //! ## Advanced variables and custom functions //! This time, instead of using a map, we will use a callback function, //! which defines custom variables, functions, and array-like objects: //! //! ``` //! fn main() -> Result<(), fasteval::Error> { //! let mut cb = |name:&str, args:Vec<f64>| -> Option<f64> { //! let mydata : [f64; 3] = [11.1, 22.2, 33.3]; //! match name { //! // Custom constants/variables: //! "x" => Some(3.0), //! "y" => Some(4.0), //! //! // Custom function: //! "sum" => Some(args.into_iter().sum()), //! //! // Custom array-like objects: //! // The `args.get...` code is the same as: //! // mydata[args[0] as usize] //! // ...but it won't panic if either index is out-of-bounds. //! "data" => args.get(0).and_then(|f| mydata.get(*f as usize).copied()), //! //! // A wildcard to handle all undefined names: //! _ => None, //! } //! }; //! //! let val = fasteval::ez_eval("sum(x^2, y^2)^0.5 + data[0]", &mut cb)?; //! // | | | //! // | | square-brackets act like parenthesis //! // | variables are like custom functions with zero args //! // custom function //! //! assert_eq!(val, 16.1); //! //! // Let's explore some of the hidden complexities of variables: //! // //! // * There's really no difference between a variable and a custom function. //! // Therefore, variables can receive arguments too, //! // which will probably be ignored. //! // Therefore, these two expressions evaluate to the same thing: //! // eval("x + y") == eval("x(1,2,3) + y(x, y, sum(x,y))") //! // ^^^^^ ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ //! // All this stuff is ignored. //! // //! // * Built-in functions take precedence WHEN CALLED AS FUNCTIONS. //! // This design was chosen so that builtin functions do not pollute //! // the variable namespace, which is important for some applications. //! // Here are some examples: //! // pi -- Uses the custom 'pi' variable, NOT the builtin 'pi' function. //! // pi() -- Uses the builtin 'pi' function even if a custom variable is defined. //! // pi(1,2,3) -- Uses the builtin 'pi' function, and produces a WrongArgs error //! // during parse because the builtin does not expect any arguments. //! // x -- Uses the custom 'x' variable. //! // x() -- Uses the custom 'x' variable because there is no 'x' builtin. //! // x(1,2,3) -- Uses the custom 'x' variable. The args are ignored. //! // sum -- Uses the custom 'sum' function with no arguments. //! // sum() -- Uses the custom 'sum' function with no arguments. //! // sum(1,2) -- Uses the custom 'sum' function with two arguments. //! //! Ok(()) //! } //! ``` //! //! ## Re-use the Slab to go faster //! If we perform the parse and eval ourselves (without relying on the 'ez' //! interface), then we can re-use the [`Slab`](slab/index.html) allocation for //! subsequent parsing and evaluations. This avoids a significant amount of //! slow memory operations: //! //! ``` //! use std::collections::BTreeMap; //! use fasteval::Evaler; // use this trait so we can call eval(). //! fn main() -> Result<(), fasteval::Error> { //! let parser = fasteval::Parser::new(); //! let mut slab = fasteval::Slab::new(); //! //! // See the `parse` documentation to understand why we use `from` like this: //! let expr_ref = parser.parse("x + 1", &mut slab.ps)?.from(&slab.ps); //! //! // Let's evaluate the expression a couple times with different 'x' values: //! //! let mut map : BTreeMap<String,f64> = BTreeMap::new(); //! map.insert("x".to_string(), 1.0); //! let val = expr_ref.eval(&slab, &mut map)?; //! assert_eq!(val, 2.0); //! //! map.insert("x".to_string(), 2.5); //! let val = expr_ref.eval(&slab, &mut map)?; //! assert_eq!(val, 3.5); //! //! // Now, let's re-use the Slab for a new expression. //! // (This is much cheaper than allocating a new Slab.) //! // The Slab gets cleared by 'parse()', so you must avoid using //! // the old expr_ref after parsing the new expression. //! // One simple way to avoid this problem is to shadow the old variable: //! //! let expr_ref = parser.parse("x * 10", &mut slab.ps)?.from(&slab.ps); //! //! let val = expr_ref.eval(&slab, &mut map)?; //! assert_eq!(val, 25.0); //! //! Ok(()) //! } //! ``` //! //! ## Compile to go super fast! //! If you plan to evaluate an expression just one or two times, then you //! should parse-eval as shown in previous examples. But if you expect to //! evaluate an expression three or more times, you can dramatically improve //! your performance by compiling. The compiled form is usually more than 10 //! times faster than the un-compiled form, and for constant expressions it is //! usually more than 200 times faster. //! ``` //! use std::collections::BTreeMap; //! use fasteval::Evaler; // use this trait so we can call eval(). //! use fasteval::Compiler; // use this trait so we can call compile(). //! fn main() -> Result<(), fasteval::Error> { //! let parser = fasteval::Parser::new(); //! let mut slab = fasteval::Slab::new(); //! let mut map = BTreeMap::new(); //! //! let expr_str = "sin(deg/360 * 2*pi())"; //! let compiled = parser.parse(expr_str, &mut slab.ps)?.from(&slab.ps).compile(&slab.ps, &mut slab.cs); //! for deg in 0..360 { //! map.insert("deg".to_string(), deg as f64); //! // When working with compiled constant expressions, you can use the //! // eval_compiled*!() macros to save a function call: //! let val = fasteval::eval_compiled!(compiled, &slab, &mut map); //! eprintln!("sin({}°) = {}", deg, val); //! } //! //! Ok(()) //! } //! ``` //! //! ## Unsafe Variables //! If your variables *must* be as fast as possible and you are willing to be //! very careful, you can build with the `unsafe-vars` feature (`cargo build //! --features unsafe-vars`), which enables pointer-based variables. These //! unsafe variables perform 2x-4x faster than the compiled form above. This //! feature is not enabled by default because it slightly slows down other //! non-variable operations. //! ``` //! use fasteval::Evaler; // use this trait so we can call eval(). //! use fasteval::Compiler; // use this trait so we can call compile(). //! fn main() -> Result<(), fasteval::Error> { //! let parser = fasteval::Parser::new(); //! let mut slab = fasteval::Slab::new(); //! //! // The Unsafe Variable will use a pointer to read this memory location: //! // You must make sure that this variable stays in-scope as long as the //! // expression is in-use. //! let mut deg : f64 = 0.0; //! //! // Unsafe Variables must be registered before 'parse()'. //! // (Normal Variables only need definitions during the 'eval' phase.) //! unsafe { slab.ps.add_unsafe_var("deg".to_string(), °); } // `add_unsafe_var()` only exists if the `unsafe-vars` feature is enabled: `cargo test --features unsafe-vars` //! //! let expr_str = "sin(deg/360 * 2*pi())"; //! let compiled = parser.parse(expr_str, &mut slab.ps)?.from(&slab.ps).compile(&slab.ps, &mut slab.cs); //! //! let mut ns = fasteval::EmptyNamespace; // We only define unsafe variables, not normal variables, //! // so EmptyNamespace is fine. //! //! for d in 0..360 { //! deg = d as f64; //! let val = fasteval::eval_compiled!(compiled, &slab, &mut ns); //! eprintln!("sin({}°) = {}", deg, val); //! } //! //! Ok(()) //! } //! ``` //! //! ## Let's Develop an Intuition of `fasteval` Internals //! In this advanced example, we peek into the Slab to see how expressions are //! represented after the 'parse' and 'compile' phases. //! ``` //! use fasteval::Compiler; // use this trait so we can call compile(). //! fn main() -> Result<(), fasteval::Error> { //! let parser = fasteval::Parser::new(); //! let mut slab = fasteval::Slab::new(); //! //! let expr_str = "sin(deg/360 * 2*pi())"; //! let expr_ref = parser.parse(expr_str, &mut slab.ps)?.from(&slab.ps); //! //! // Let's take a look at the parsed AST inside the Slab: //! // If you find this structure confusing, take a look at the compilation //! // AST below because it is simpler. //! assert_eq!(format!("{:?}", slab.ps), //! r#"ParseSlab{ exprs:{ 0:Expression { first: EStdFunc(EVar("deg")), pairs: [ExprPair(EDiv, EConstant(360.0)), ExprPair(EMul, EConstant(2.0)), ExprPair(EMul, EStdFunc(EFuncPi))] }, 1:Expression { first: EStdFunc(EFuncSin(ExpressionI(0))), pairs: [] } }, vals:{} }"#); //! // Pretty-Print: //! // ParseSlab{ //! // exprs:{ //! // 0:Expression { first: EStdFunc(EVar("deg")), //! // pairs: [ExprPair(EDiv, EConstant(360.0)), //! // ExprPair(EMul, EConstant(2.0)), //! // ExprPair(EMul, EStdFunc(EFuncPi))] //! // }, //! // 1:Expression { first: EStdFunc(EFuncSin(ExpressionI(0))), //! // pairs: [] } //! // }, //! // vals:{} //! // } //! //! let compiled = expr_ref.compile(&slab.ps, &mut slab.cs); //! //! // Let's take a look at the compilation results and the AST inside the Slab: //! // Notice that compilation has performed constant-folding: 1/360 * 2*pi = 0.017453292519943295 //! // In the results below: IFuncSin(...) represents the sin function. //! // InstructionI(1) represents the Instruction stored at index 1. //! // IMul(...) represents the multiplication operator. //! // 'C(0.017...)' represents a constant value of 0.017... . //! // IVar("deg") represents a variable named "deg". //! assert_eq!(format!("{:?}", compiled), //! "IFuncSin(InstructionI(1))"); //! assert_eq!(format!("{:?}", slab.cs), //! r#"CompileSlab{ instrs:{ 0:IVar("deg"), 1:IMul(InstructionI(0), C(0.017453292519943295)) } }"#); //! //! Ok(()) //! } //! ``` //! //! # Safety //! //! `fasteval` is designed to evaluate untrusted expressions safely. By //! default, an expression can only perform math operations; there is no way //! for it to access other types of operations (like network or filesystem or //! external commands). Additionally, we guard against malicious expressions: //! //! * Expressions that are too large (greater than 4KB). //! * Expressions that are too-deeply nested (greater than 32 levels). //! * Expressions with too many values (greater than 64). //! * Expressions with too many sub-expressions (greater than 64). //! //! All limits can be customized at parse time. If any limits are exceeded, //! [`parse()`](https://docs.rs/fasteval/latest/fasteval/parser/struct.Parser.html#method.parse) will return an //! [Error](https://docs.rs/fasteval/latest/fasteval/error/enum.Error.html). //! //! Note that it *is* possible for you (the developer) to define custom functions //! which might perform dangerous operations. It is your responsibility to make //! sure that all custom functionality is safe. //! //! //! # Performance Benchmarks //! //! These benchmarks were performed on 2019-12-25. Merry Christmas. //! //! Here are links to all the libraries/tools included in these benchmarks: //! //! * [fasteval (this library)](https://github.com/likebike/fasteval) //! * [caldyn](https://github.com/Luthaf/caldyn) //! * [rsc](https://github.com/codemessiah/rsc) //! * [meval](https://github.com/rekka/meval-rs) //! * [calc](https://github.com/redox-os/calc) //! * [tinyexpr (Rust)](https://github.com/kondrak/tinyexpr-rs) //! * [tinyexpr (C)](https://github.com/codeplea/tinyexpr) //! * [bc](https://www.gnu.org/software/bc/) //! * [python3](https://www.python.org/) //! //! ## Charts //! Note that the following charts use logarithmic scales. Therefore, tiny //! visual differences actually represent very significant performance //! differences. //! //! **Performance of evaluation of a compiled expression:** //!  //! //! **Performance of one-time interpretation (parse and eval):** //!  //! //! **Performance of compiled Unsafe Variables, compared to the tinyexpr C library (the //! only other library in our test set that supports this mode):** //!  //! //! **Performance of interpreted Unsafe Variables, compared to the tinyexpr C library (the //! only other library in our test set that supports this mode):** //!  //! //! ## Summary //! //! The impressive thing about these results is that `fasteval` consistently //! achieves the fastest times across every benchmark and in every mode of //! operation (interpreted, compiled, and unsafe). It's easy to create a //! design to claim the #1 spot in any one of these metrics by sacrificing //! performance in another, but it is difficult to create a design that can be //! #1 across-the-board. //! //! Because of the broad and robust performance advantages, `fasteval` is very //! likely to be an excellent choice for your dynamic evaluation needs. //! //! ## Benchmark Descriptions & Analysis //! ```text //! * simple = `3 * 3 - 3 / 3` //! This is a simple test with primitive binary operators. //! Since the expression is quite simple, it does a good job of showing //! the intrinsic performance costs of a library. //! Results: //! * For compiled expressions, `fasteval` is 6x as fast as the closest //! competitor (caldyn) because the `eval_compiled!()` macro is able to //! eliminate all function calls. If the macro is not used and a //! normal `expr.eval()` function call is performed instead, then //! performance is very similar to caldyn's. //! * For interpreted expressions, `fasteval` is 2x as fast as the //! tinyexpr C lib, and 3x as fast as the tinyexpr Rust lib. //! This is because `fasteval` eliminates redundant work and memory //! allocation during the parse phase. //! //! * power = `2 ^ 3 ^ 4` //! `2 ^ (3 ^ 4)` for `tinyexpr` and `rsc` //! This test shows the associativity of the exponent operator. //! Most libraries (including `fasteval`) use right-associativity, //! but some libraries (particularly tinyexpr and rsc) use //! left-associativity. //! This test is also interesting because it shows the precision of a //! library's number system. `fasteval` just uses f64 and therefore truncates //! the result (2417851639229258300000000), while python, bc, and the //! tinyexpr C library produce a higher precision result //! (2417851639229258349412352). //! Results: //! Same as the 'simple' case. //! //! * variable = `x * 2` //! This is a simple test of variable support. //! Since the expression is quite simple, it shows the intrinsic //! performance costs of a library's variables. //! Results: //! * The tinyexpr Rust library does not currently support variables. //! * For safe compiled evaluation, `fasteval` is 4.4x as fast as the closest //! competitor (caldyn). //! * For safe interpretation, `fasteval` is 3.3x as fast as the closest //! competitor (caldyn). //! * For unsafe variables, `fasteval` is 1.2x as fast as the //! tinyexpr C library. //! //! * trig = `sin(x)` //! This is a test of variables, built-in function calls, and trigonometry. //! Results: //! * The tinyexpr Rust library does not currently support variables. //! * The `calc` library does not support trigonometry. //! * For safe compiled evaluation, `fasteval` is 2.6x as fast as the //! closest competitor (caldyn). //! * For safe interpretation, `fasteval` is 2.3x as fast as the closest //! competitor (caldyn). //! * Comparing unsafe variables with the tinyexpr C library, //! `fasteval` is 8% slower for compiled expressions (tinyexpr uses a //! faster `sin` implementation) and 4% faster for interpreted //! expressions (`fasteval` performs less memory allocation). //! //! * quadratic = `(-z + (z^2 - 4*x*y)^0.5) / (2*x)` //! This test demonstrates a more complex expression, involving several //! variables, some of which are accessed more than once. //! Results: //! * The tinyexpr Rust library does not currently support variables. //! * For safe compiled evaluation, `fasteval` is 2x as fast as the //! closest competitor (rsc). //! * For safe interpretation, `fasteval` is 3.7x as fast as the //! closest competitor (caldyn). //! * Comparing unsafe variables with the tinyexpr C library, //! `fasteval` is the same speed for compiled expressions, //! and 1.2x as fast for interpretation. //! //! * large = `((((87))) - 73) + (97 + (((15 / 55 * ((31)) + 35))) + (15 - (9)) - (39 / 26) / 20 / 91 + 27 / (33 * 26 + 28 - (7) / 10 + 66 * 6) + 60 / 35 - ((29) - (69) / 44 / (92)) / (89) + 2 + 87 / 47 * ((2)) * 83 / 98 * 42 / (((67)) * ((97))) / (34 / 89 + 77) - 29 + 70 * (20)) + ((((((92))) + 23 * (98) / (95) + (((99) * (41))) + (5 + 41) + 10) - (36) / (6 + 80 * 52 + (90))))` //! This is a fairly large expression that highlights parsing costs. //! Results: //! * Since there are no variables in the expression, `fasteval` and //! `caldyn` compile this down to a single constant value. That's //! why these two libraries are so much faster than the rest. //! * For compiled evaluation, `fasteval` is 6x as fast as `caldyn` //! because it is able to eliminate function calls with the //! `eval_compiled!()` macro. //! * For interpretation, `fasteval` is 2x as fast as the closest //! competitor (rsc). //! * Comparing unsafe variables with the tinyexpr C library, //! `fasteval` is 3x as fast for compiled evaluation, and //! 1.2x as fast for interpretation. //! ``` //! //! ## Methodology //! I am running Ubuntu 18.04 on an Asus G55V (a 2012 laptop with Intel Core i7-3610QM CPU @ 2.3GHz - 3.3GHz). //! //! All numeric results can be found in `fasteval/benches/bench.rs`. //! //! See the [detailed post about my benchmarking methology]{http://likebike.com/posts/How_To_Write_Fast_Rust_Code.html#how-to-measure} //! on my blog. //! //! # How is `fasteval` so fast? //! //! A variety of techniques are used to optimize performance: //! * [Minimization of memory allocations/deallocations](http://likebike.com/posts/How_To_Write_Fast_Rust_Code.html#reduce-redundancy-mem); //! I just pre-allocate a large `Slab` during initialization. //! * Elimination of redundant work, [especially when parsing](http://likebike.com/posts/How_To_Write_Fast_Rust_Code.html#reduce-redundancy-logic). //! * Designed using ["Infallible Data Structures"](http://likebike.com/posts/How_To_Write_Fast_Rust_Code.html#reduce-redundancy-data), which eliminate all corner cases. //! * Compilation: Constant Folding and Expression Simplification. //! Boosts performance up to 1000x. //! * Profile-driven application of inlining. Don't inline too much or too little. //! Maximizes data locality. //! * Localize variables. Use [`RUSTFLAGS="--emit=asm"`](http://likebike.com/posts/How_To_Write_Fast_Rust_Code.html#emit-asm) as a guide. //! //! # Can `fasteval` be faster? //! //! Yes, but not easily, and not by much. //! //! To boost the 'eval' phase, we would really need to perform compilation to //! machine code, which is difficult and non-portable across platforms, and //! increases the likelyhood of security vulnerabilities. Also, the potential //! gains are limited: We already run at //! half-the-speed-of-compiled-optimized-Rust for constant expressions (the //! most common case). So for constant expressions, the most you could gain //! from compilation-to-machine-code is a 2x performance boost. We are already //! operating close to the theoretical limit! //! //! It is possible to perform faster evaluation of non-constant expressions by //! introducing more constraints or complexity: //! * If I introduce a 'const' var type, then I can transform variable //! expressions into constant expressions. I don't think this would be //! useful-enough in real-life to justify the extra complexity (but please //! tell me if your use-case would benefit from this). //! * Evaluation could be paralellized (with a more complex design). //! //! It is possible to boost overall speed by improving the parsing algorithm //! to produce a Reverse Polish Notation AST directly, rather than the currennt //! infix AST which is then converted to RPN during compilation. However, this //! isn't as simple as just copying the Shunting-Yard algorithm because I //! support more advanced (and customizable) syntax (such as function calls and //! strings), while Shunting-Yard is designed only for algebraic expressions. //! //! //! # Future Work //! Here are some features that I might add in the future: //! //! * Dynamic `sprintf` string formatting for the `print()` built-in expression function. //! * FFI so this library can be used from other languages. //! * Ability to copy the contents of a `Slab` into a perfectly-sized container //! (`PackedSlab`) to reduce wasted memory. //! * Support for other number types other than `f64`, such as Integers, Big Integers, //! Arbitrary Precision Numbers, Complex Numbers, etc. like [rclc](https://crates.io/crates/rclc). //! //! # List of Projects that use `fasteval` //! //! [Send me a message](mailto:christopher@likebike.com) if you would like to list your project here. //! //! * [koin.cx](http://koin.cx/) //! * [robit](#coming-soon) //! * [openpinescript](#coming-soon) //! * [The Texas Instruments MW-83 Plus Scientific Microwave Oven](https://raw.githubusercontent.com/likebike/fasteval/master/examples/scientific-microwave-ti-mw-83-plus.jpg) //#![feature(test)] //#![warn(missing_docs)] //// Keeping for reference: // #![cfg_attr(feature="nightly", feature(slice_index_methods))] pub mod error; #[macro_use] pub mod slab; pub mod parser; #[macro_use] pub mod compiler; pub mod evaler; pub mod evalns; pub mod ez; pub use self::error::Error; pub use self::parser::{Parser, Expression, ExpressionI, Value, ValueI}; pub use self::compiler::{Compiler, Instruction::{self, IConst}, InstructionI}; #[cfg(feature="unsafe-vars")] pub use self::compiler::Instruction::IUnsafeVar; pub use self::evaler::Evaler; pub use self::slab::Slab; pub use self::evalns::{EvalNamespace, Cached, EmptyNamespace, StringToF64Namespace, StrToF64Namespace, StringToCallbackNamespace, StrToCallbackNamespace, LayeredStringToF64Namespace, CachedCallbackNamespace}; pub use self::ez::ez_eval; // TODO: Convert `match`es to `if let`s for performance boost.